5. How does NP-Movement with predicates like ‘seem’ occur?

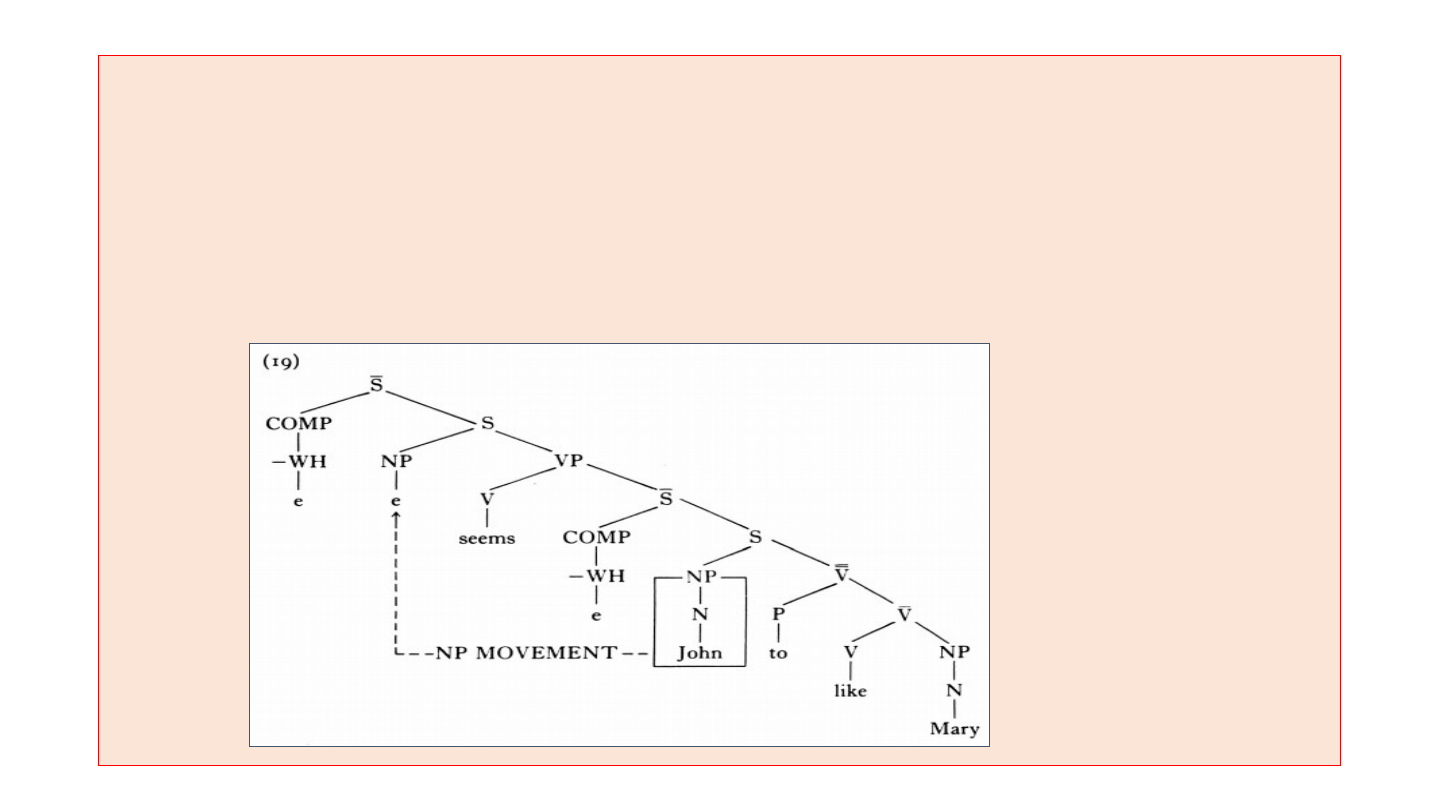

The operation of NP-Movement in the seem-sentence (18) can be schematized by

the tree diagram of (19), which is the underlying structure. The subordinate subject

NP ‘John’ moves into the empty NP-position in the main clause(seem-clause):

(18) John seems to like Mary ( ← surface structure)

( ← underlying structure)

(20) NP-Movement

Move an NP into

an

empty NP-position

▶ The empty NP-position of ‘seems’ in (19) is underlying empty, and the NP con-

cerned

is filled by the lexical expression ‘John’. But here, the important thing is that the NP

‘John’ must have a case in any syntactic structures. In the underlying structure (19), if

the NP ‘John’ is not moved into the subject position in seems-clause, the ‘John’ has no

case and any interpretation as well, accordingly, being ungrammatical.

▶ Because the subordinate clause(like-clause) is untensed, the verb ‘like’ cannot assign

a nominative case to the NP ‘John’. So the ‘John’ needs to move into the empty NP-

position in the main tensed clause(seems-clause), which is eligible to give a case to

the subject NP. Therefore, the NP-Movement of ‘John’ is required obligatorily.

▶ Every NP can be interpreted in a sentence as long as having a appropriate

case.

In any syntactic structures, the cases of NPs must be satisfied for the interpretation

of NP. Accordingly, the property of the semantic interpretation is significantly related

to syntactic structures.

♣ In NP-Movement, lexical item NPs cannot move to the filled NP-positon by any

other lexical item. Suppose that the most likely candidate to fill the NP is it.

If so, the ‘John’ should not move into the filled NP-positon.

(21) It seems that John likes Mary

To be more precise, in (21), ‘John’ in subordinate tensed clause have a nominative case,

and so

the ‘John’ is not needed to be moved to the main clause. Of course, since the subject

positon in the main clause is filled by ‘it’, the movement of ‘John’ to that position is

banned.

This account is supported by the constraint (23) for NP-Movement:

(23) No rule in any natural language can replace a constituent containing

lexical material by any other constituent

So, the sentence (21) that has no NP-movement is grammatically well-formed.

6. Adjunction vs. Substitution

WH-Movement is an adjunction rule whereby one constituent is adjoined

to COMP;

by contrast, NP-Movement is a substitution rule whereby one constituent is

substituted

for an empty NP category.

An empty node constituent can be replaced by another same kind of constituent.

So a grammar of English must provide a principled account of why the NP moves into

an empty NP-position – the moved NP comes to occupy an empty NP-node –

as constrained with the substitution rule (24):

(24) Structure-Preserving Constraint

A constituent can only be moved by a substitution rule into another

category of the same type.

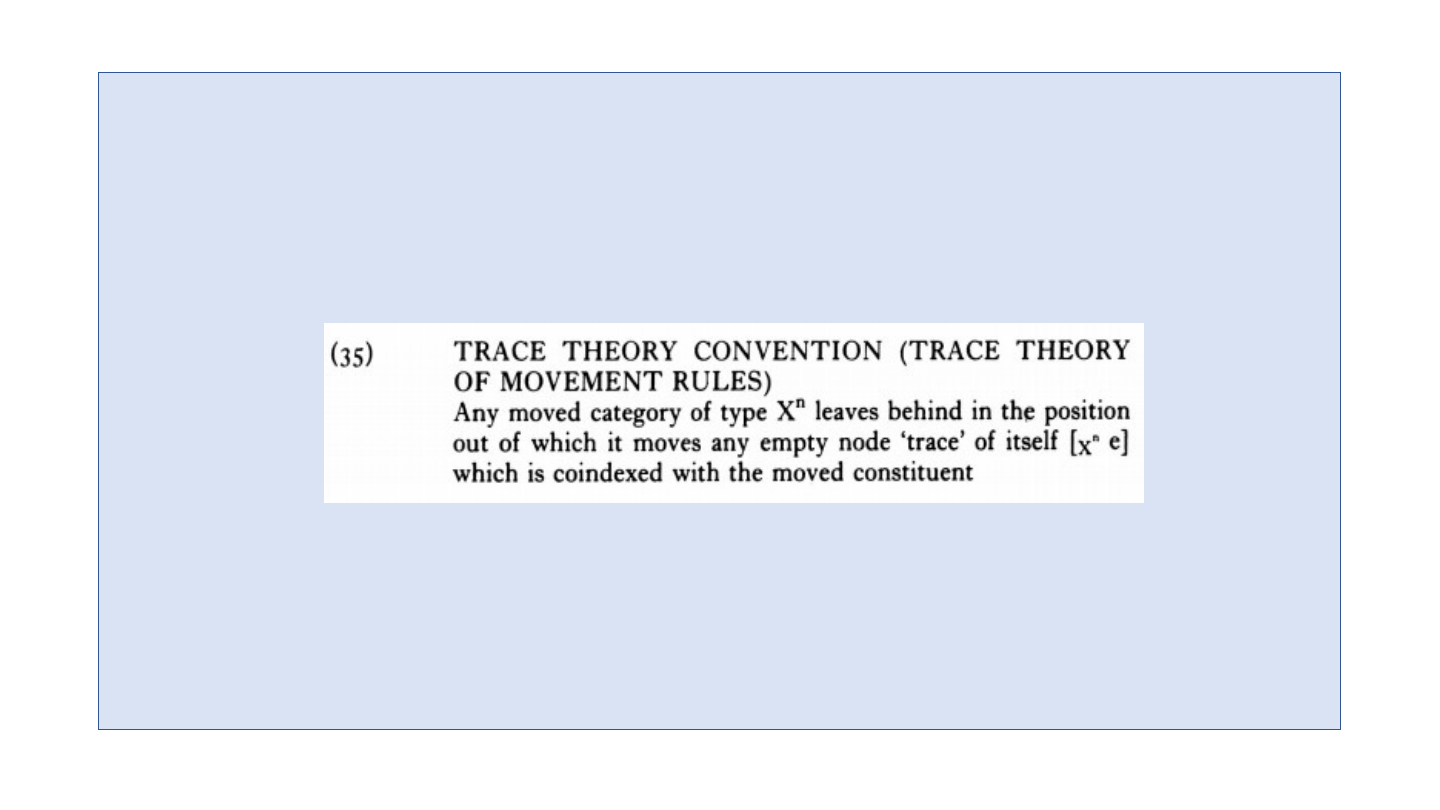

7. Trace Theory Convention

Movement rules leave behind a coindexed empty node trace of themselves; this is

known as Trace Theory. The wanna-contraction might be well explained by Trace Theory.

(29) You might want who to win? (underlying structure)

(30) Who might you want to win? (surface structure)

(31) *Who might you wanna win? (wanna-contraction in surface structure)

(29) S’ (30) S’

COMP S COMP S

[+WH] NP VP [+WH] NP VP

N AUX V’ NP COMP N AUX V’

might V S’ who1 e might V S’

you want COMP S you want COMP S

[+WH] NP VP [+WH] NP VP

who N to V’ t1 N to V’

(who) V Wh-Movement (t1) V

win win

The NP ‘who’ originates in the position of the subject in the win-clause, and moves

to the COMP by the adjunction rule as a wh-word in the same clause. And then the

‘who’ is adjoined to the higher COMP again, when the trace(t) leaves behind in the empty

node NP by the movement of NP. This assumption can be conditioned by Trace

Theory Convention (35):

In (30), the trace(t1) is coindexed with the moved ‘who1’, showing the preservation of

the same category as a coreferential NP. The coindexed t1 cannot be ignored since it is

an exact NP category. Therefore, wanna-contraction is not possible in (30). The

Trace

Theory Convention is effective for the account of wanna-contractions.

8. All Movement Rules leave behind a Trace

All movement rules including both NP-Movement and WH-Movement leave behind

a coindexed empty category (=trace) when they move a constituent. For an indirect

question, the surface structure of a sentence (38) would be represented in detail as in (39),

with a trace(t) of ‘what’. The wh-word ‘what’ leaves behind a coindexed empty category.

The empty category [NP2 e] means a trace (t).

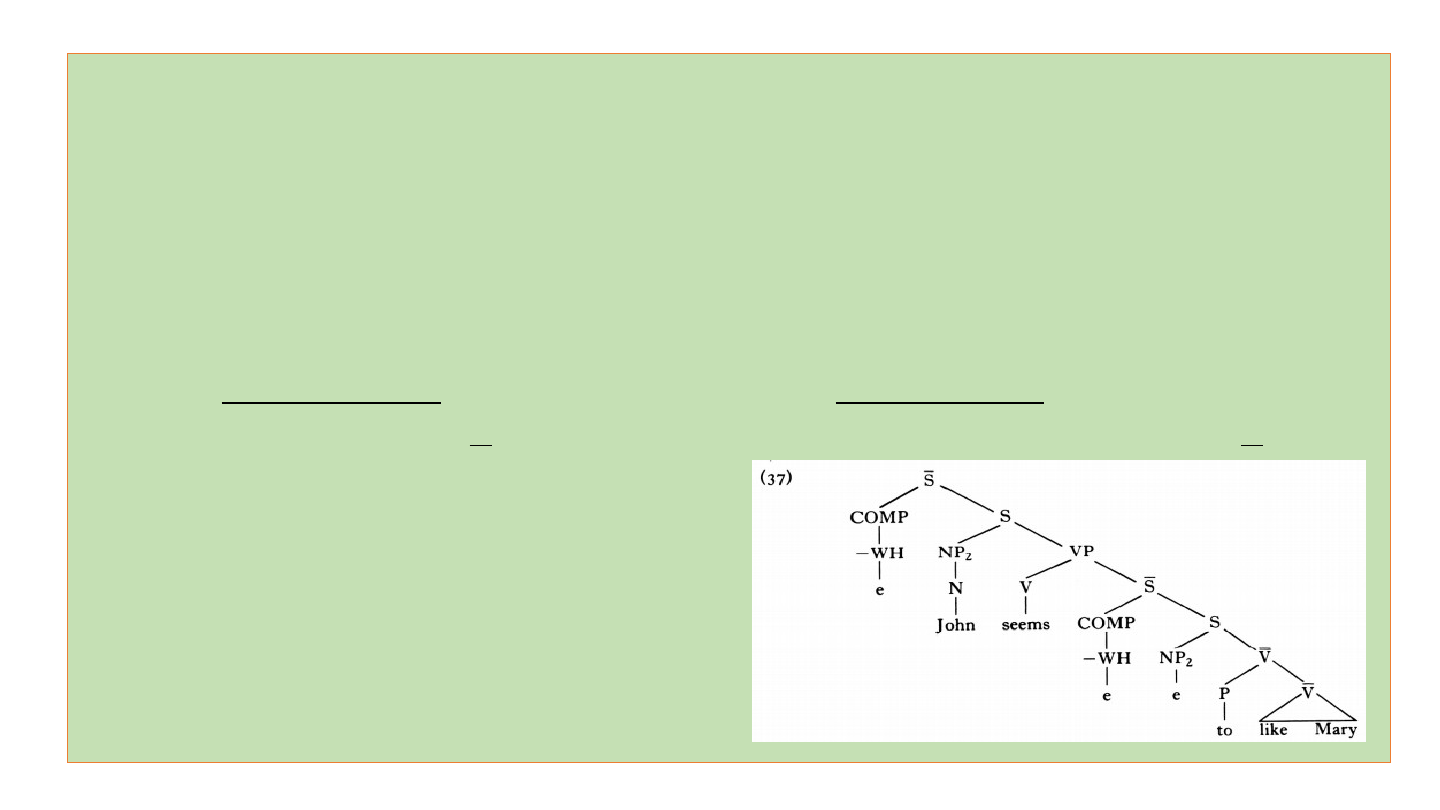

WH-Movement NP-Movement

(38) I wonder what he did (37) [NP2 John] seems [NP2 e] to like Mary

(39) I wonder [NP2 what] he did [NP2 e]

(37) shows that the NP-Movement of ‘John’ leaves

behind a coindexed empty category [NP2 e] (=trace).

(The coindexed category has the same interpretation)