11. PRO constituent

Chomsky assumes that in sentences like:

(62) John tried to frighten Mary -> surface structure(S-structure)

The infinitive complement to frighten Mary has an empty pronominal NP subject

which he designates as PRO:

(63) Johni tried [s’ comp PROi to frighten Mary] -> underlying structure(D-struc-

ture)

The abstract PRO must contain inherent person, number and gender feature.

(64) John tried [s’ PRO to be a good soldier/*good soldiers]

=> PRO must be third person masculine singular in (64).

◈

PRO never carries case, and PRO can never be governed.

Lexical NPs can only occur in NP-positions where they are both governed and

case-marked. Therefore, PRO and lexical NP are in complementary distribution.

(65) PRO-CONDITION

Any sentence containing PRO in a position where it is governed

(or case-marked) is ill-formed

barrier

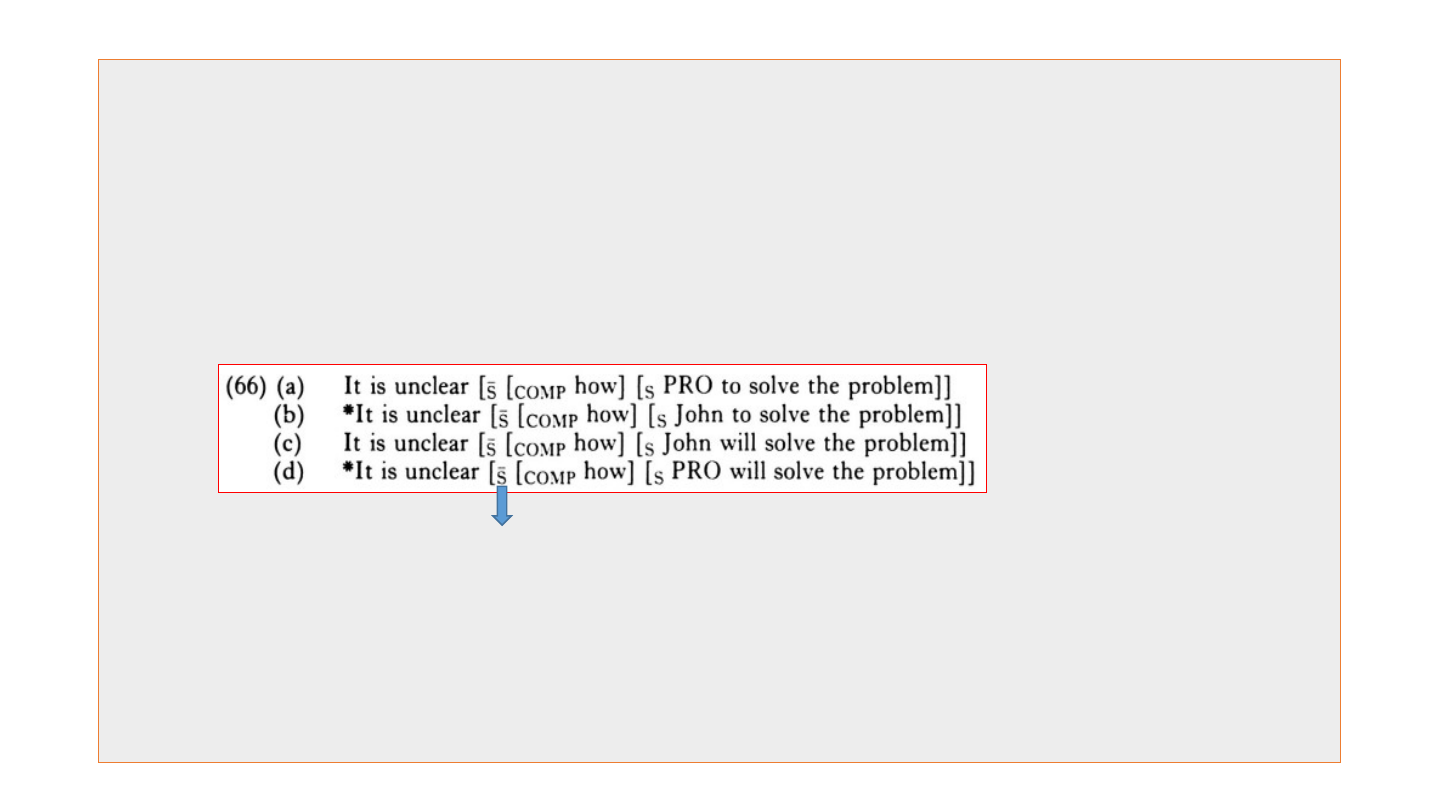

(66a) : PRO cannot be governed by unclear across the barrier S-bar, satisfying PRO-Condition.

(66b) : Lexical NP John is ungoverned and caseless, violating Case Filter.

(66c) : John is governed and assigned nominative case by the Tense auxiliary will, satisfying

Case Filter.

(66d) : PRO is governed and assigned nominative case by will, violating PRO-Condition.

◈ Case Theory indirectly predicts that PRO can occur only as the subject

of a bare infinitive.

(68) (a) John tried to leave

(b) *John considers to be successful

(69) (a) John tried [s’ [COMP e] [s PRO to leave]]

The node S’ is a barrier and PRO is ungoverned by tried.

(b) *John considers [s PRO to be successful]]

The node S isn’t a barrier and PRO is governed by considers.

PRO-Condition is violated.

The verb considers governs PRO because there is no intervening

S-bar. Considers has no S-bar by S-bar Deletion in D-structure.

12. Case-marking in Raising Constructions

(72) John seems to like Mary -> Surface Structure

(73) seems [s’ [s John to like Mary] -> Deep Structure

John in (73) fails to be assigned any case at all by seems because seems is not a transitive

verb.

And also seems doesn’t govern John since there is underlyingly a barrier S-bar.

But remarkably, a subject John needs a nominative case regardless of case-assigning from seems.

In (73), the nominative case of John is not satisfied in the infinitive clause.

Accordingly, John in underlying structure (73) should be raised to the subject position to get

a nominative case from TENSE in tensed clause, satisfying Case Filter.

In NP-movement like (73), case-marking applies at S-structure, not at D-structure:

(74) John2 seems [s [NP2 e] to like Mary]

The NP-movement in (73) is obligatory for NP’s case checking.

If NP-movement doesn’t occur like (75), John has no case and violates Case Filter.

(75) *It seems John to like Mary.

It seems [s’ [s John to like Mary ]]

♣ Case Theory provides us with a principled account of why it seems that NP-movement

is

obligatory with Raising predictates like seem, likely, etc.

(77) John was criticized

(78) was criticized John -> underlying structure

(79) John2 was criticized [NP2 e] -> surface structure with raising of John, satisfying Case Fil-

ter

(80) *It was criticized John -> violating Case Filter

The passive verb cannot assign a case to the NP John

(82) NP-Trace Condition

The trace of an NP Movement cannot be case-marked.

(83) (a) It is necessary for John to leave

(b) *John is necessary for to leave

(85) *John2 is necessary [s’ [COMP for] [s [NP2 e] to leave ]] -> underlying structure of (83)

NP-trace

◈ In (85), the trace of John [NP2 e] is assigned objective case, since it is governed by the

prepositional complementiser for. But NP-trace cannot carry case-marking by (82).

So (83b) that undergoes NP-movement is ill-formed, violating NP-Trace Condition.