[3] Agreement: English has a rule of person-number agreement whereby a verb has to

agree

in person and number with the NP (Noun Phrase) immediately preceding it:

(52) (a) He might say this boy likes/*like Mary

(b) He might say those boys like/*likes Mary

wh-echo question

(53) (a) He might say which boy likes/*like Mary?

(b) He might say which boys like/*likes Mary?

Wh-movement

(54) (a) Which boy might he say likes/*like Mary?

(b) Which boys might he say like/*likes Mary?

The sentences in (54) derive from an underlying structure of (53). So wh-words(=NP) in

surface structure of (54) have already agreed with their verbs in the number. There exists

the underlying structure of a sentence before the surface structure of it, with a

transformation of WH-Movement mapping the base structure into the corresponding

surface structure.

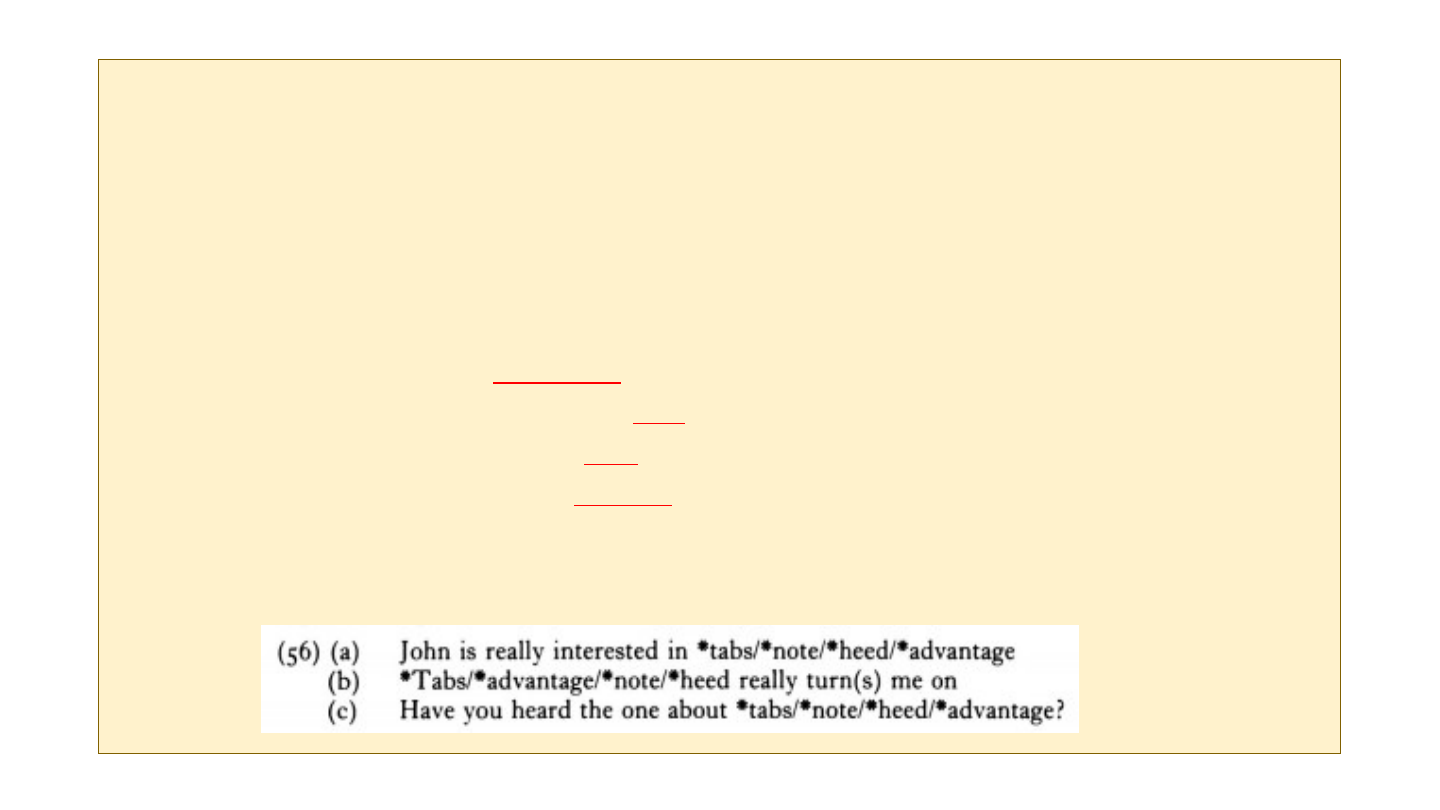

[4] Idiom Chunk Argument: This is a fourth argument in support of postulating a

rule of

WH-Movement. English has a class of Noun Phrases which are

highly

restricted in their distribution, in the sense that they generally oc-

cur

only in conjunction with some specific verb:

(55) (a) John took advantage of her generosity

(b) The government keep tabs on his operations

(c) I want you to take note of what I say

(d) The soldiers paid homage to their dead

In (55), the red-colored phrases are all idiom chunk, with a special meaning.

The underlined NPs such as advantage, tabs, note, homage are idiom chunk

NPs.

They don’t have the same syntactic freedom of distribution as other NPs like (56).

The NPs in the idiom chunks are limited to the distribution in the sentences of (56).

The synonyms of the items concerned are not subject to the same restriction, as we can

see from comparing heed with its close synonym attention as in (57). But the phrase

as an idiom chunck ‘pay heed to’ has the same meaning with ‘pay attention to’.

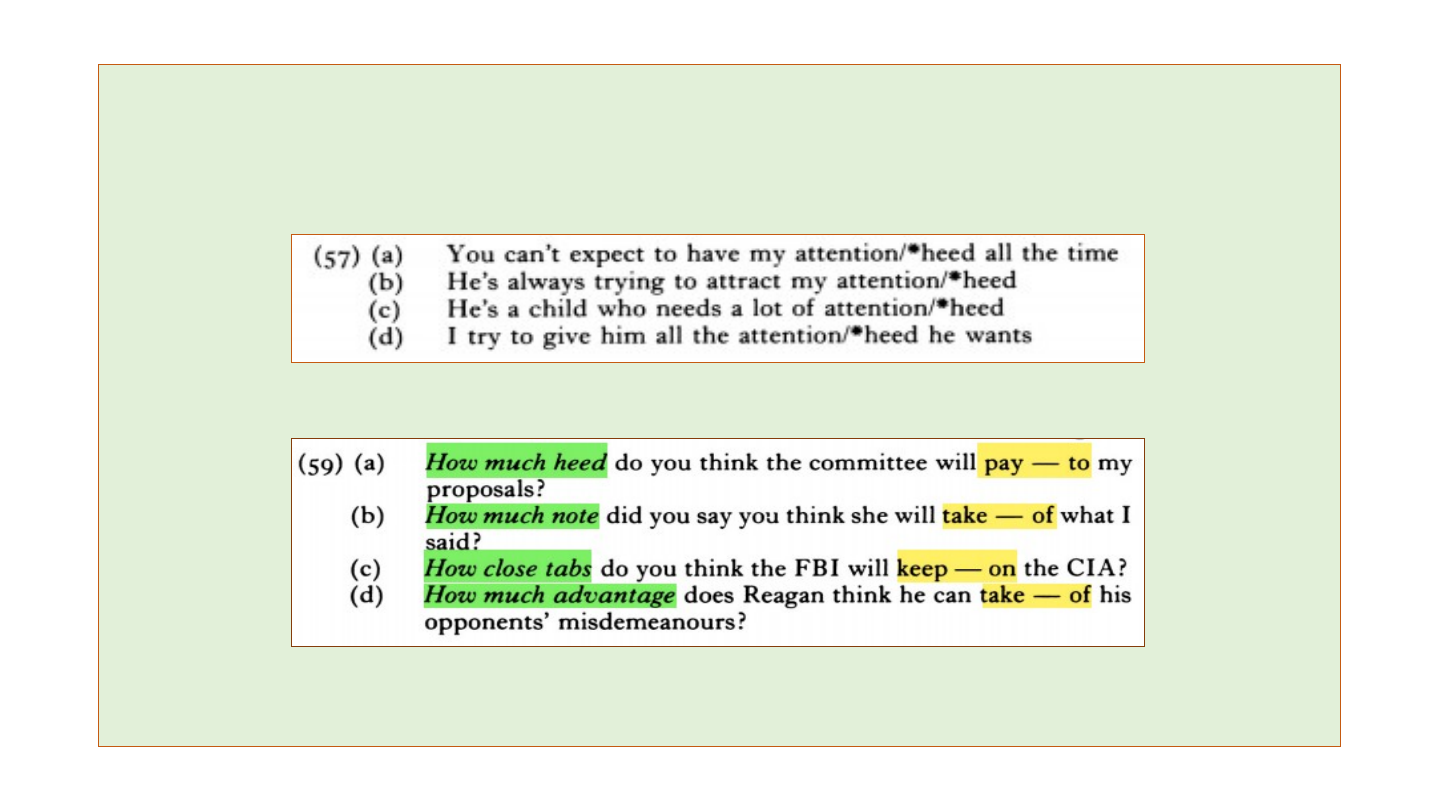

Consider how we are to handle sentences in (59):

How are we account for the grammaticality of sentences (59), in which the idiom chunk

NP

actually occurs sentence-initially?

▶ The idiom chunk NPs in sentences of (59) originate in the position in underlying

structure, and are subsequently moved into sentence-initial position by WH-Movement

in surface structure. We can then say that the sentences in (59) are grammatical

precisely because the wh-idiom chunk phrase originated to the immediate right

of

the verb of which it is a complement in each case.

▶ Any such analysis presupposes both an abstract level of underlying syntactic

structure

and a transformation of WH-Movement mapping the underlying structure

into the

surface structure.

♣ It is important that the distribution of syntactic items(words) in underlying

structure affect the grammaticality of them in surface structure, and in this

process, transformational rules operate.

5. Possibility or Impossibility of Contraction:

[1] Syntactic Property in Phonological facts

In (61), it can be freely either the full form Jean is or the contracted form Jean’s.

(61) (a) Mary is good at hockey, and Jean is good at volleyball

(b) Mary is good at hockey, and Jean‘s good at volleyball

However, if we omit the second occurrence of good in (61), verb contraction is impossible:

(62) (a) Mary is good at hockey, and Jean is at volleyball

(b) *Mary is good at hockey, and Jean’s at volleyball

Why should the contraction be possible in (61) (b), but not in (62) (b)? For the answer, we

might need the rule of (63):

(63) Contracted forms cannot be used when there is a ‘missing’ constituent immedi-

ately

following.

=>

In (62), the adjective ‘good’ is missing from the position marked , and hence

contraction is not possible

.

The contraction is also blocked in Wh-Movement structure:

(64) (a) How good do you think Mary is at Linguistics?

(b) *How good do you think Mary’s at Linguistics?

The wh-phrase ‘How good’ originates in the blank position and is subsequently

moved out of that position by WH-Movement to the front of the sentence. At this

time, the missing constituent occurs as ‘How good’. So according to (63), the con-

traction

Mary’s is ungrammatical as in (64) (b).

[2] Wanna Contraction: In some varieties of American English, want to can be con-

tracted

to wanna as in (65):

(65) (a) I want to win

(b) I wanna win

For some speakers of this type of dialect, wanna-contraction is possible as in (66):

(66) (a) Who do you want to beat ? (← You want to beat who? (underlying struc-

ture))

(b) Who do you wanna beat ?

But the wanna-contraction in the sentence (67) is not possible:

(67) (a) Who do you want to win? (← You want who to win? (underlying structure))

(b) *Who do you wanna win?

▶ For the appropriate explanation about wanna-contraction, we need to state again that

the notion underlying structure seems to be central to any account of (66)-(67).

In underlying structure, ‘who’ originates in each case in the blank position, and is

subsequently moved into initial position by WH-Movement. But the contraction is

blocked in (67) because ‘who’ originates between want and to, thereby blocking

wanna-contraction.

By contrast, in (66) ‘who’ originates after the verb beat, not intervening between

want and to, thereby the contraction is not blocked.

▶ In conclusion, a rule of WH-Movement closely relates the underlying structure to

the corresponding surface structure.