CHAPTER 12

Chemical Bonding

1.

A chemical bond is a force that holds groups of two or more atoms together and makes them func

tion as a unit.

2.

The bond energy represents the energy required to break a chemical bond.

3.

An ionic bond is created when a metallic element reacts with a non-metallic element.

4.

A covalent bond represents the sharing of pairs of electrons between nuclei.

5.

In Cl2, the bonding is pure covalent with the electron pair shared equally between the two chlorin

e atoms. In HCl there is a shared pair of electrons, but the shared pair is drawn more closely to th

e chlorine atom, making the bond is polar.

6.

In H2 and HF, the bonding is covalent in nature, with an electron pair being shared between the at

oms. In H2, the two atoms are identical (the sharing is equal); in HF, the two atoms are different (t

he sharing is unequal) and as a result the bond is polar. Both of these are in marked contrast to the

situation in NaF: NaF is an ionic compound—an electron has been completely transferred from s

odium to fluorine, producing separate ions.

7.

electronegativity

8.

A bond is polar if the centers of positive and negative charge do not coincide at the same point. T

he bond has a negative end and a positive end. Polar bonds will exist in any molecule with nonide

ntical bonded atoms (although the molecule, as a whole, may not be polar if the bond dipoles can

cel each other). Two simple examples are HF and HCl: in both cases, the negative center of charg

e is closer to the halogen atom.

9.

large

10.

The level of polarity in a polar covalent bond is determined by the difference in electronegativity

of the atoms in the bond.

11.

In general, an element farther to the right in a given period or an element closer to the top of a giv

en group is more electronegative.

a.

H is most electronegative; K is least electronegative

b.

F is most electronegative; Na is least electronegative

c.

F is most electronegative; B is least electronegative

12.

a.

At is most electronegative, Cs is least electronegative

b.

Sr is most electronegative, Ba and Ra have the same electronegativities

c.

O is most electronegative, Rb is least electronegative

238

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

13.

Generally, covalent bonds between atoms of different elements are polar.

a.

covalent

b.

ionic

c.

polar covalent

14.

Generally, covalent bonds between atoms of different elements are polar.

a.

covalent

b.

polar covalent

c.

ionic

15.

For a bond to be polar covalent, the atoms involved in the bond must have different electronegati

vities (must be of different elements).

a.

polar covalent (atoms of different elements)

b.

polar covalent (atoms of different elements)

c.

nonpolar covalent (atoms of the same element)

d.

nonpolar covalent (atoms of the same element)

16.

For a bond to be polar covalent, the atoms involved in the bond must have different electronegati

vities (must be of different elements).

a.

nonpolar covalent (atoms of the same element)

b.

nonpolar covalent (atoms of the same element)

c.

nonpolar covalent (atoms of the same element)

d.

polar covalent (atoms of different elements)

17.

The degree of polarity of a polar covalent bond is indicated by the magnitude of the difference in

electronegativities of the elements involved: the larger the difference in electronegativity, the mor

e polar the bond. Electronegativity differences are given in parentheses below:

a.

H–F (1.9); H–Cl (0.9); the H–F bond is more polar

b.

H–Cl (0.9); H–I (0.4); the H–Cl bond is more polar

c.

H–Br (0.7); H–Cl (0.9); the H–Cl bond is more polar

d.

H–I (0.4); H–Br (0.7); the H–Br bond is more polar

18.

The degree of polarity of a polar covalent bond is indicated by the magnitude of the difference in

electronegativities of the elements involved: the larger the difference in electronegativity, the mor

e polar the bond. Electronegativity differences are given in parentheses below:

a.

O–Cl (0.5); O–Br(0.7); the O–Br bond is more polar

b.

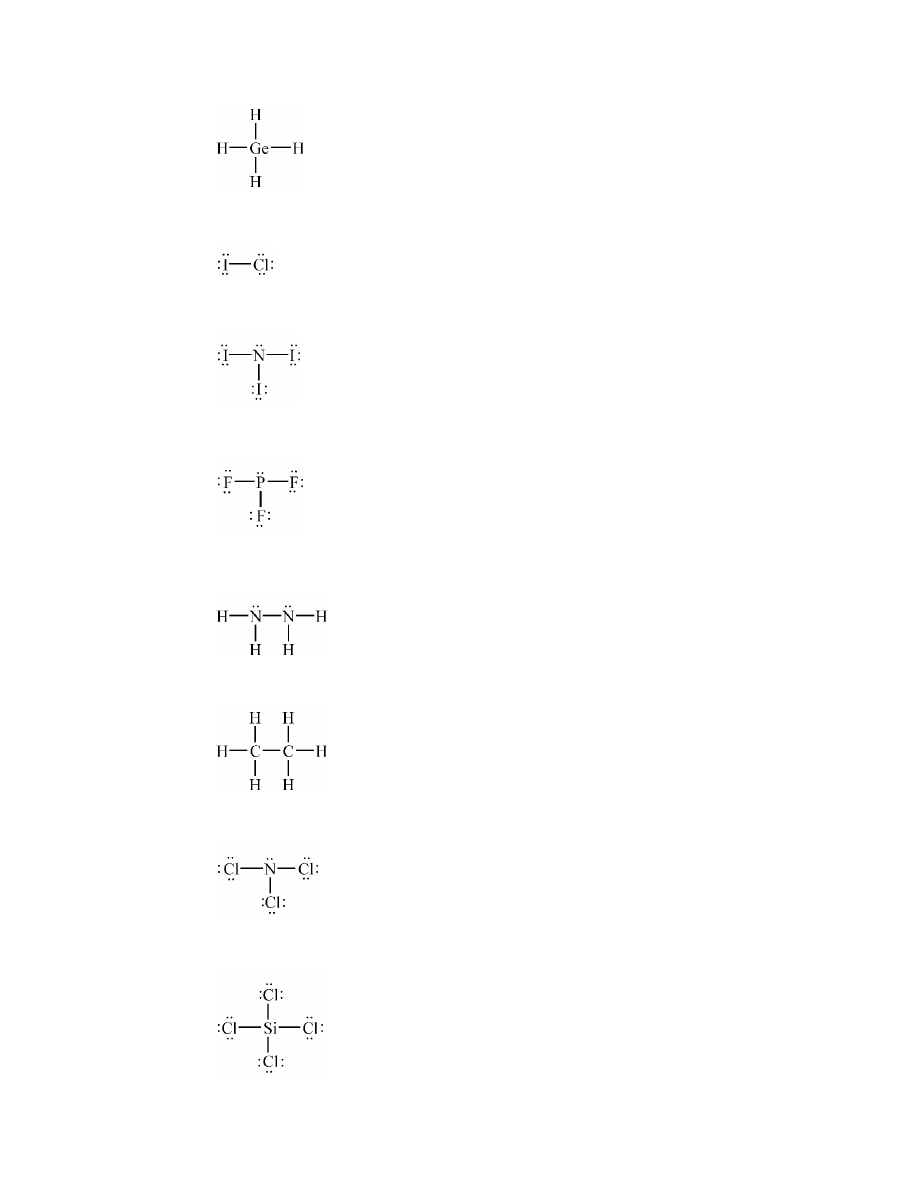

N–O (0.5); N–F (1.0); the N–F bond is more polar

c.

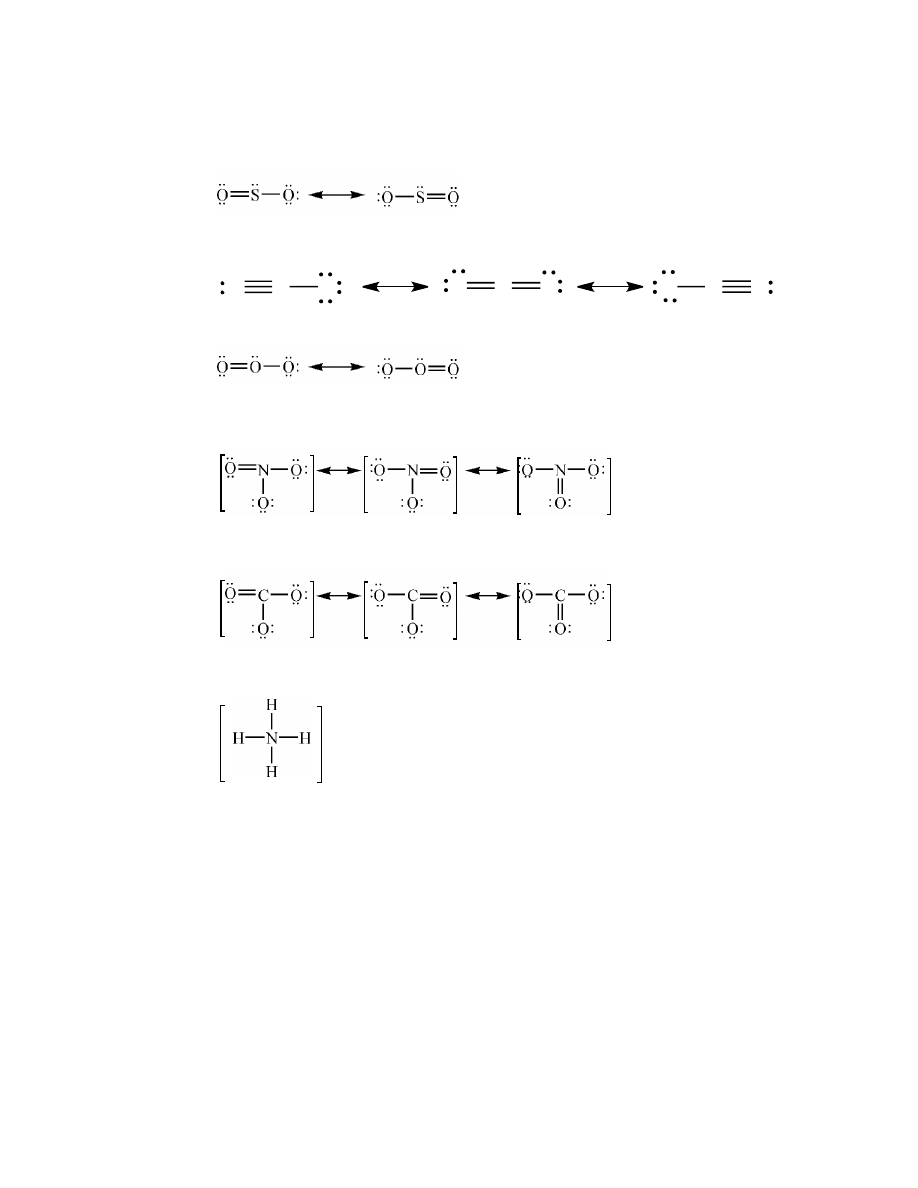

P–S (0.4); P–O (1.4); the P–O bond is more polar

d.

H–O (1.4); H–N (0.9); the H–O bond is more polar

239

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

19.

The larger the difference in electronegativity between two atoms, the more ionic character the bo

nd possesses. Electronegativity differences are given in parentheses below:

a.

Na–F (3.1); Na–I (1.6); the Na–F bond has more ionic character

b.

Ca–S (1.5); Ca–O (2.5); the Ca–O bond has more ionic character

c.

Li–Cl (2.0); Cs–Cl(2.3); the Cs–Cl bond has more ionic character

d.

Mg–N (1.8); Mg–P (0.9); the Mg–N bond has more ionic character

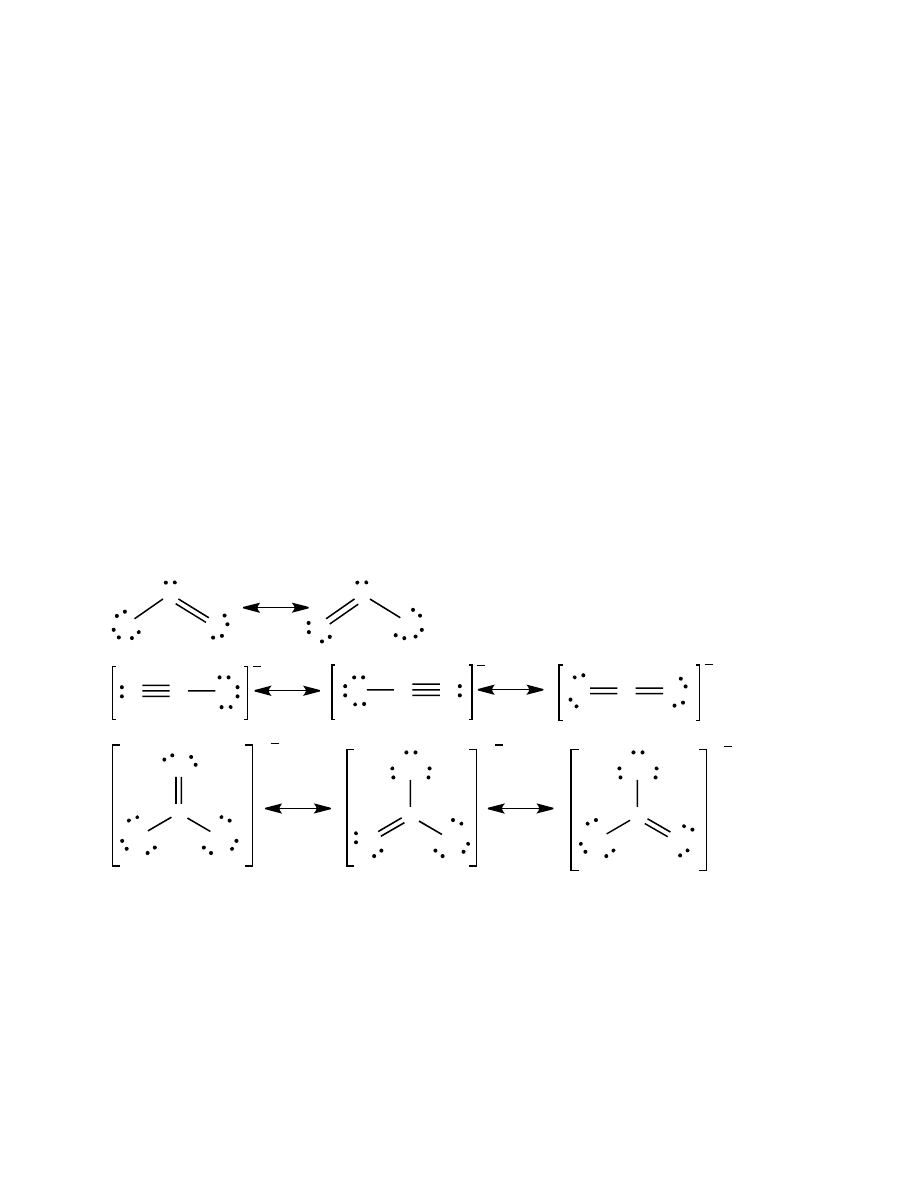

20.

The greater the electronegativity difference between two atoms, the more ionic will be the bond b

etween those two atoms.

a.

Na–N

b.

K–P

c.

Na–Cl

d.

Mg–Cl

21.

A dipole moment is an electrical effect that occurs in a molecule that has separate centers of posit

ive and negative charge. The simplest examples of molecules with dipole moments would be diat

omic molecules involving two different elements. For example:

+ C O –

+ N O –

+ Cl F –

+ Br Cl –

22.

The presence of strong bond dipoles and a large overall dipole moment in water make it a polar s

ubstance overall. Among the properties of water dependent on its dipole moment are its freezing

point, melting point, vapor pressure, and its ability to dissolve many substances.

23.

In a diatomic molecule containing two different elements, the more electronegative atom will be t

he negative end of the molecule, and the less electronegative atom will be the positive end.

a.

chlorine

b.

oxygen

c.

fluorine

24.

In a diatomic molecule containing two different elements, the more electronegative atom will be t

he negative end of the molecule, and the less electronegative atom will be the positive end.

a.

H

b.

Cl

c.

I

25.

In the figures, the arrow points toward the more electronegative atom.

a.

+ C F –

b.

+ Si C –

240

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

c.

+ C O –

d.

+ B C –

26.

In the figures, the arrow points toward the more electronegative atom.

a.

+ P S –

b.

+ S F –

c.

+ S Cl –

d.

+ S Br –

27.

In the figures, the arrow points toward the more electronegative atom.

a.

+ Si H –

b.

P–H

The atoms have very nearly the same electronegativity, so there is a very small, if

any, dipole moment.

c.

+ H S –

d.

+ H Cl –

28.

In the figures, the arrow points toward the more electronegative atom.

a.

+ H C –

b.

+ N O –

c.

+ S N –

d.

+ C N –

29.

When forming ionic bonds, the element forming the positive ion loses enough electrons to have t

he same configuration as the previous noble gas. The element forming the negative ion gains eno

ugh electrons to have the same configuration as the next noble gas. When forming covalent comp

ounds, electrons are shared in such a way that as many atoms as possible in the molecule have a c

onfiguration analogous to a noble gas

30.

preceding

31.

gaining

32.

Atoms in covalent molecules gain a configuration like that of a noble gas by sharing one or more

pairs of electrons between atoms: such shared pairs of electrons “belong” to each of the atoms of t

he bond at the same time. In ionic bonding, one atom completely gives over one or more electron

s to another atom, and the resulting ions behave independently of one another.

33.

a.

Chlorine is in Group 7 and has configuration 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p5. Chlorine would be

expected to gain one electron to become the Cl– ion. The Cl– ion has an electron configu

ration analogous to the noble gas Ar: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6

241

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

b.

Strontium is in Group 2 and has configuration 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p6 5s2.

Strontium would be expected to lose two electrons to become the Sr2+ ion. The Sr2+ ion

has an electron configuration analogous to the noble gas Kr: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10

4p6.

c.

Oxygen is in Group 6 and has electron configuration 1s2 2s2 2p4. Oxygen would be

expected to gain two electrons to become the O2– ion. The O2– ion has an electron

configuration analogous to the noble gas Ne: 1s2 2s2 2p6

d.

Rubidium is in Group 1 and has electron configuration 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p6 5s1.

Rubidium would be expected to lose one electron to become the Rb+ ion. The Rb+ ion has

an electron configuration analogous to the noble gas Kr: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p6.

34.

a.

Br–, Kr (Br has one electron less than Kr)

b.

Cs+, Xe (Cs has one electron more than Xe)

c.

P3–, Ar (P has three fewer electrons than Ar)

d.

S2–, Ar (S has two fewer electrons than Ar)

35.

a.

Na+, Mg2+, Al3+; 1s2 2s2 2p6

b.

Li+, Be2+; 1s2

c.

K+, Ca2+ from the A group elements; 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6

d.

Rb+, Sr2+ from the A group elements; 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p6

36.

Atoms or ions with the same number of electrons are said to be isoelectronic.

a.

Cl–, S2–, P3–

b.

F–, O2–, N3–

c.

Br–, Se2–, As3–

d.

I–, Te2–

37.

a.

Al2S3: Al has three electrons more than a noble gas; S has two electrons fewer than a

noble gas.

b.

RaO: Ra has two electrons more than a noble gas; O has two electrons fewer than a noble

gas.

c.

CaF2: Ca has two electrons more than a noble gas; F has one electron less than a noble

gas.

d.

Cs3N: Cs has one electron more than a noble gas; N has three electrons fewer than a

noble gas.

e.

RbP3

: Rb has one electron more than a noble gas; P has three electrons fewer than a

noble gas.

38.

a.

AlBr3: Al has three electrons more than a noble gas; Br has one electron less than a noble

gas.

b.

Al2O3: Al has three electrons more than a noble gas; O has two fewer electrons than a

noble gas.

242

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

c.

AlP: Al has three electrons more than a noble gas; P has three fewer electrons than a

noble gas.

d.

AlH3: Al has three electrons more than a noble gas; H has one electron less than a noble

gas.

39.

a.

Ba2+, [Xe]; S2–, [Ar]

b.

Sr2+, [Kr]; F–, [Ne]

c.

Mg2+, [Ne]; O2–, [Ne]

d.

Al3+, [Ne]; S2–, [Ar]

40.

There are many examples possible. Listed below are a few compounds that fit each situation.

a.

LiF: Li+, [He]; F–, [Ne]

b.

NaF: Na+, [Ne]; F–, [Ne]

c.

LiCl: Li+, [He]; Cl–, [Ar]

d.

NaCl: Na+, [Ne]; Cl–, [Ar]

41.

The formula of an ionic compound represents only the smallest whole number ratio of positive an

d negative ions present (the empirical formula).

42.

An ionic solid such as NaCl consists of an array of alternating positively– and negatively–charge

d ions: that is, each positive ion has as its nearest neighbors a group of negative ions, and each ne

gative ion has a group of positive ions surrounding it. In most ionic solids, the ions are packed as

tightly as possible.

43.

Positive ions are always smaller than the atoms from which they are formed, because in forming t

he ion, the valence electron shell (or part of it) is “removed” from the atom.

44.

In forming an anion, an atom gains additional electrons in its outermost (valence) shell. Additiona

l electrons in the valence shell increases the repulsive forces between electrons, so the outermost

shell becomes larger to accommodate this.

45.

Relative ionic sizes are given in Figure 12.9. Within a given horizontal row of the periodic chart,

negative ions tend to be larger than positive ions because the negative ions contain a larger numb

er of electrons in the valence shell. Within a vertical group of the periodic table, ionic size increas

es from top to bottom. In general, positive ions are smaller than the atoms they come from, where

as negative ions are larger than the atoms they come from.

a.

H

b.

N

c.

Al3+

d.

F

46.

Relative ionic sizes are given in Figure 12.9. Within a given horizontal row of the periodic chart,

negative ions tend to be larger than positive ions because the negative ions contain a larger numb

er of electrons in the valence shell. Within a vertical group of the periodic table, ionic size increas

es from top to bottom. In general, positive ions are smaller than the atoms they come from, where

243

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

as negative ions are larger than the atoms they come from. If two ions contain the same number o

f electrons, look at the nuclear charge. In general, the larger the nuclear charge, the smaller the io

n (electrons drawn closer to the nucleus).

a.

Mg

b.

K+

c.

Br–

d.

Se2–

47.

Relative ionic sizes are given in Figure 12.9. Within a given horizontal row of the periodic chart,

negative ions tend to be larger than positive ions because the negative ions contain a larger numb

er of electrons in the valence shell. Within a vertical group of the periodic table, ionic size increas

es from top to bottom. In general, positive ions are smaller than the atoms they come from, where

as negative ions are larger than the atoms they come from.

a.

Fe3+

b.

Cl

c.

Al3+

48.

Relative ionic sizes are given in Figure 12.9. Within a given horizontal row of the periodic chart,

negative ions tend to be larger than positive ions because the negative ions contain a larger numb

er of electrons in the valence shell. Within a vertical group of the periodic table, ionic size increas

es from top to bottom. In general, positive ions are smaller than the atoms they come from, where

as negative ions are larger than the atoms they come from.

a.

I

b.

F–

c.

F–

49.

Valence electrons are those found in the outermost principal energy level of the atom. The valenc

e electrons effectively represent the outside edge of the atom and are the electrons most influence

d by the electrons of another atom.

50.

When atoms form covalent bonds, they try to attain a valence electronic configuration similar to t

hat of the following noble gas element. When the elements in the first few horizontal rows of the

periodic table form covalent bonds, they will attempt to gain configurations similar to the noble g

ases helium (2 valence electrons, duet rule), and neon and argon (8 valence electrons, octet rule).

51.

noble gas electronic configuration

52.

These elements attain a total of eight valence electrons, making the valence electron configuration

s similar to those of the noble gases Ne and Ar.

53.

When two atoms in a molecule are connected by a double bond, the atoms share two pairs of elect

rons (4 electrons) in completing their outermost shells. A simple molecule containing a double bo

nd is ethene (ethylene), C2H4 (H2C::CH2).

244

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

54.

When two atoms in a molecule are connected by a triple bond, the atoms share three pairs of elect

rons (6 electrons) in completing their outermost shells. A simple molecule containing a triple bon

d is acetylene, C2H2 (H:C:::C:H).

55.

The Group in which a representative element is found indicates the number of valence electrons.

a.

I

b.

Al

c.

Xe

d.

Sr

56.

The Group in which a representative element is found indicates the number of valence electrons.

a.

Mg

b.

c.

d.

Si

57.

a.

each N provides 5; O provides 6; total valence electrons = 16

b.

each B provides 3; each H provides 1: total valence electrons = 12

c.

each C provides 4; each H provides 1; total valence electrons = 20

d.

N provides 5; each Cl provides 7; total valence electrons = 26

58.

a.

each boron provides 3; each oxygen provides 6; total valence electrons = 24

b.

carbon provides 4; each oxygen provides 6; total valence electrons = 16

c.

each carbon provides 4; each hydrogen provides 1; oxygen provides 6; total valence

electrons = 20

d.

N provides 5; each oxygen provides 6; total valence electrons = 17

59.

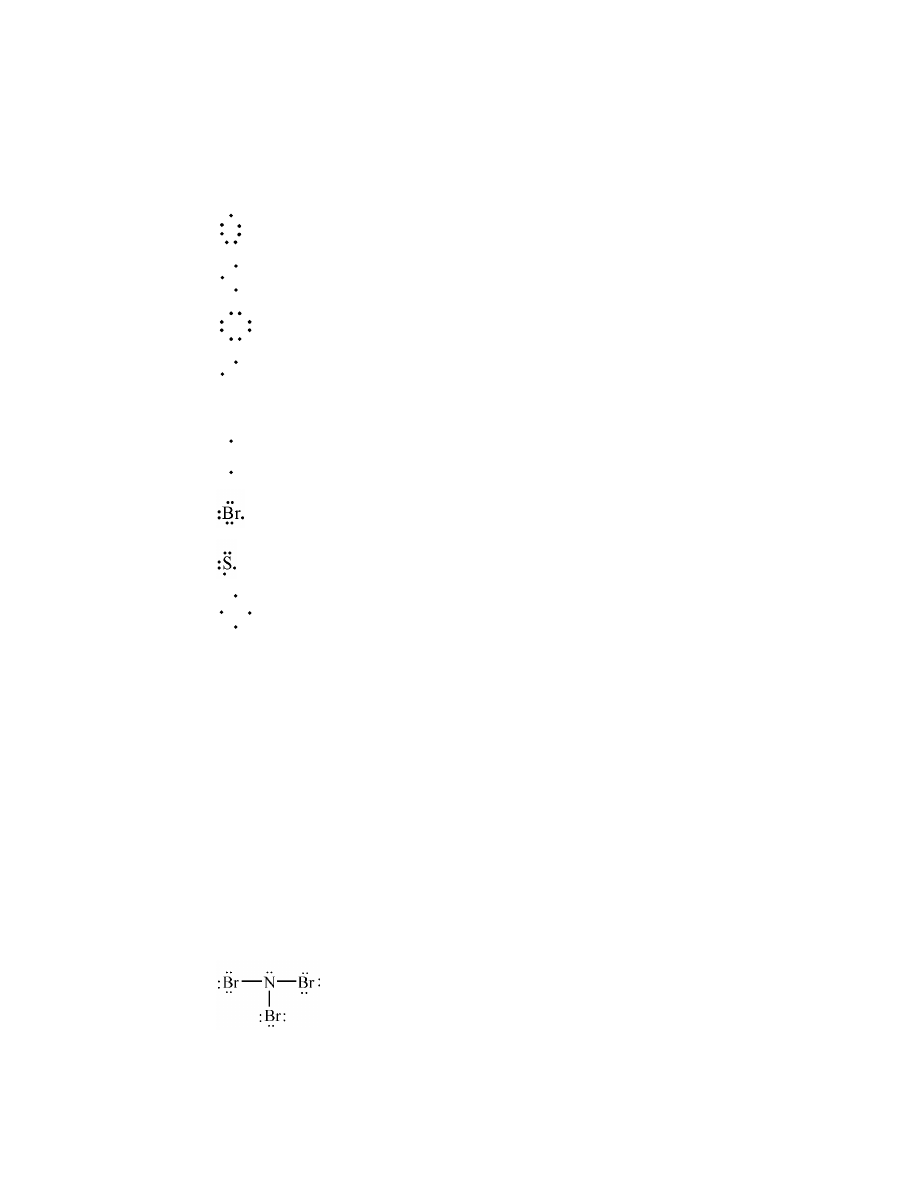

a.

Nitrogen provides 5 valence electrons; each bromine provides 7;

total valence electrons = 26.

245

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

b.

Hydrogen provides 1 valence electron; fluorine provides 7; total valence electrons = 8.

c.

Carbon provides 4 valence electrons; each bromine provides 7;

total valence electrons = 32.

d.

Each carbon provides 4 valence electrons; each hydrogen provides 1;

total valence electrons = 10.

60.

a.

Each hydrogen provides 1 valence electron; sulfur provides 6 valence electrons; total

valence electrons = 8

H

S

H

b.

Each fluorine provides 7 valence electrons; silicon provides 4 valence electrons; total

valence electrons = 32

F

Si

F

F

F

c.

Each carbon provides 4 valence electrons; each hydrogen provides 1 valence electron;

total valence electrons = 12

C

C

H

H

H

H

d.

Each carbon provides 4 valence electrons; each hydrogen provides 1 valence electron;

total valence electrons = 20

C

C

C

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

246

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

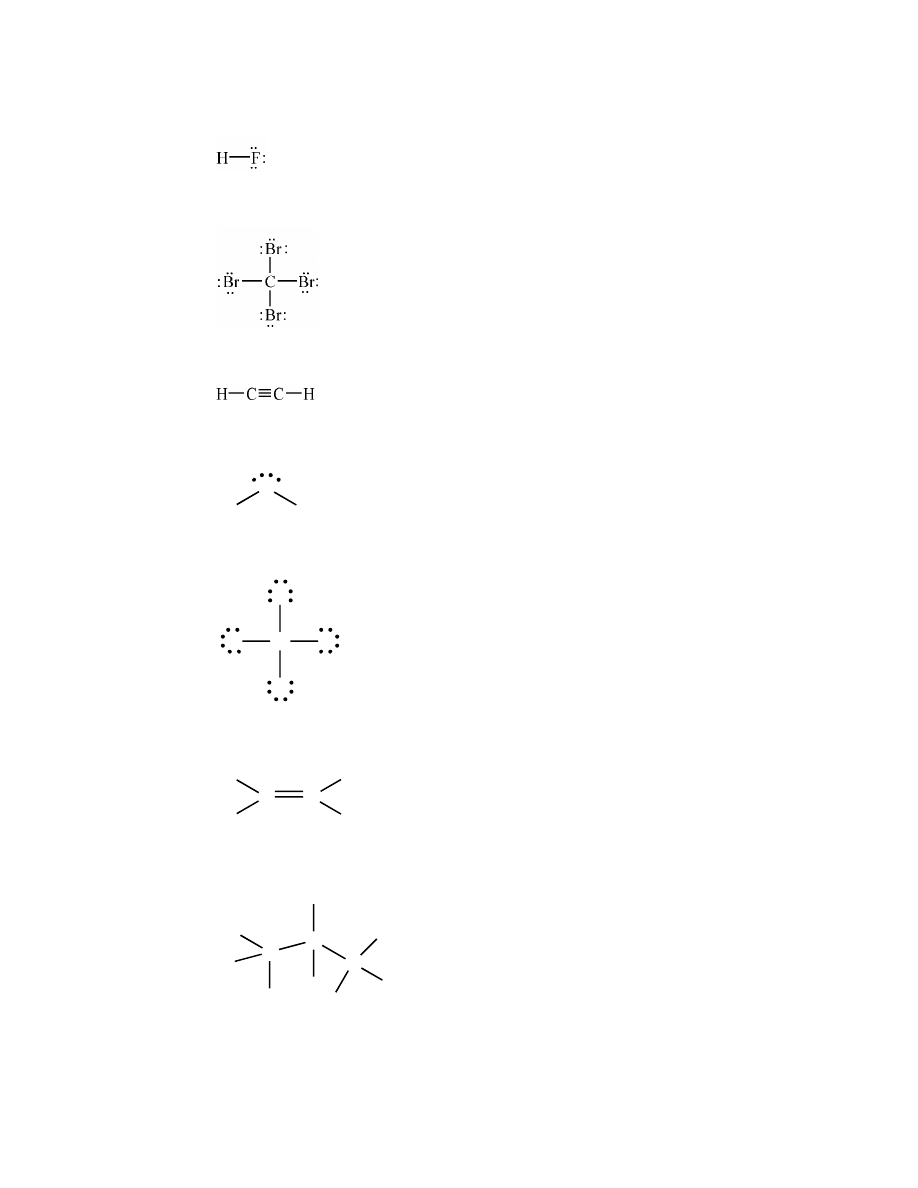

61.

a.

Each C provides 4 valence electrons. Each H provides 1 valence electron.

Total valence electrons = 14

b.

N provides 5 valence electrons. Each F provides 7 valence electrons.

Total valence electrons = 26

c.

Each C provides 4 valence electrons. Each H provides 1 valence electron.

Total valence electrons = 26

d.

Si provides 4 valence electrons. Each Cl provides 7 valence electrons.

Total valence electrons = 32

62.

a.

P provides 5 valence electrons. Each Cl provides 7 valence electrons.

Total valence electrons = 26

b.

C provides 4 valence electrons. Each Cl provides 7 valence electrons. H provides 1

valence electron.

Total valence electrons = 26

247

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

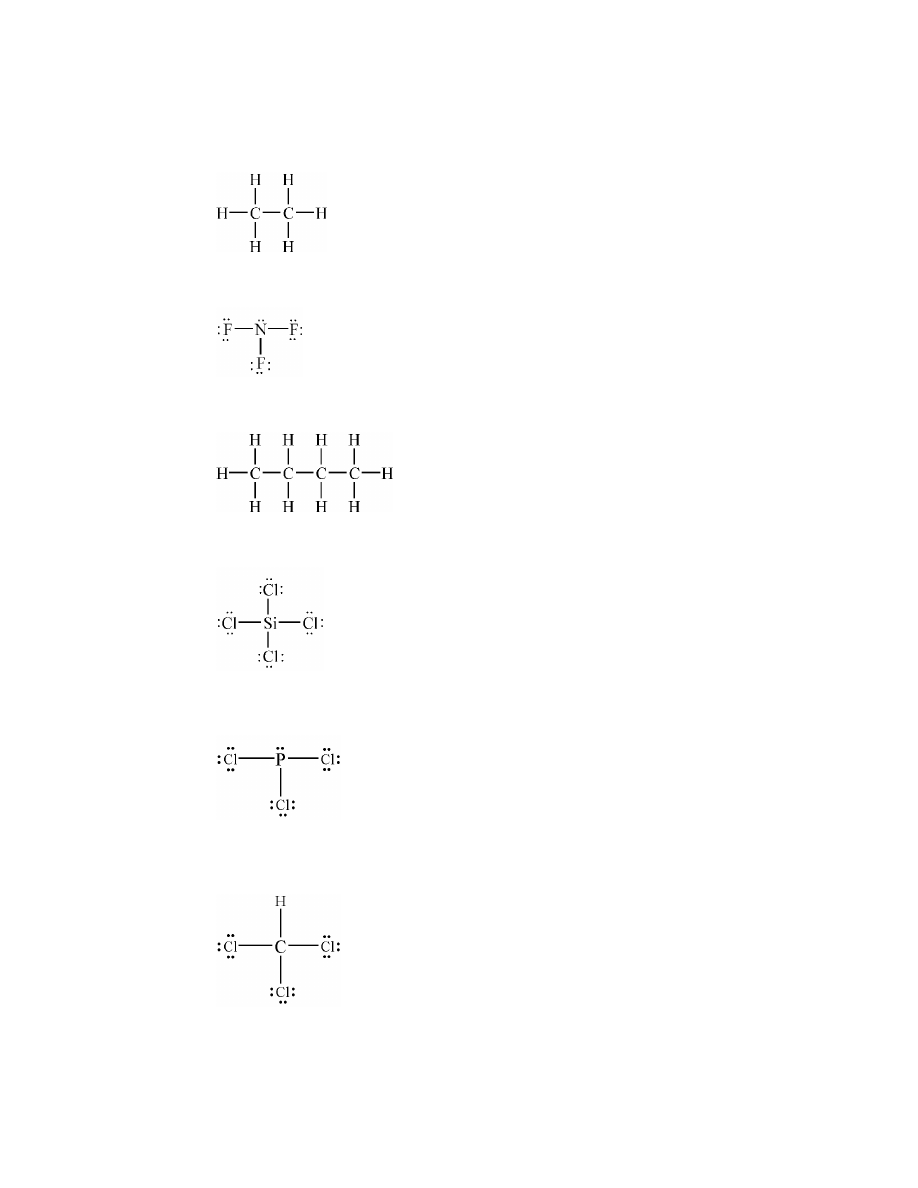

c.

Each C provides 4 valence electrons. Each H provides 1 valence electron. Each Cl

provides 7 valence electrons

Total valence electrons = 26

d.

Each N provides 5 valence electrons. Each H provides 1 valence electron.

Total valence electrons = 14

63.

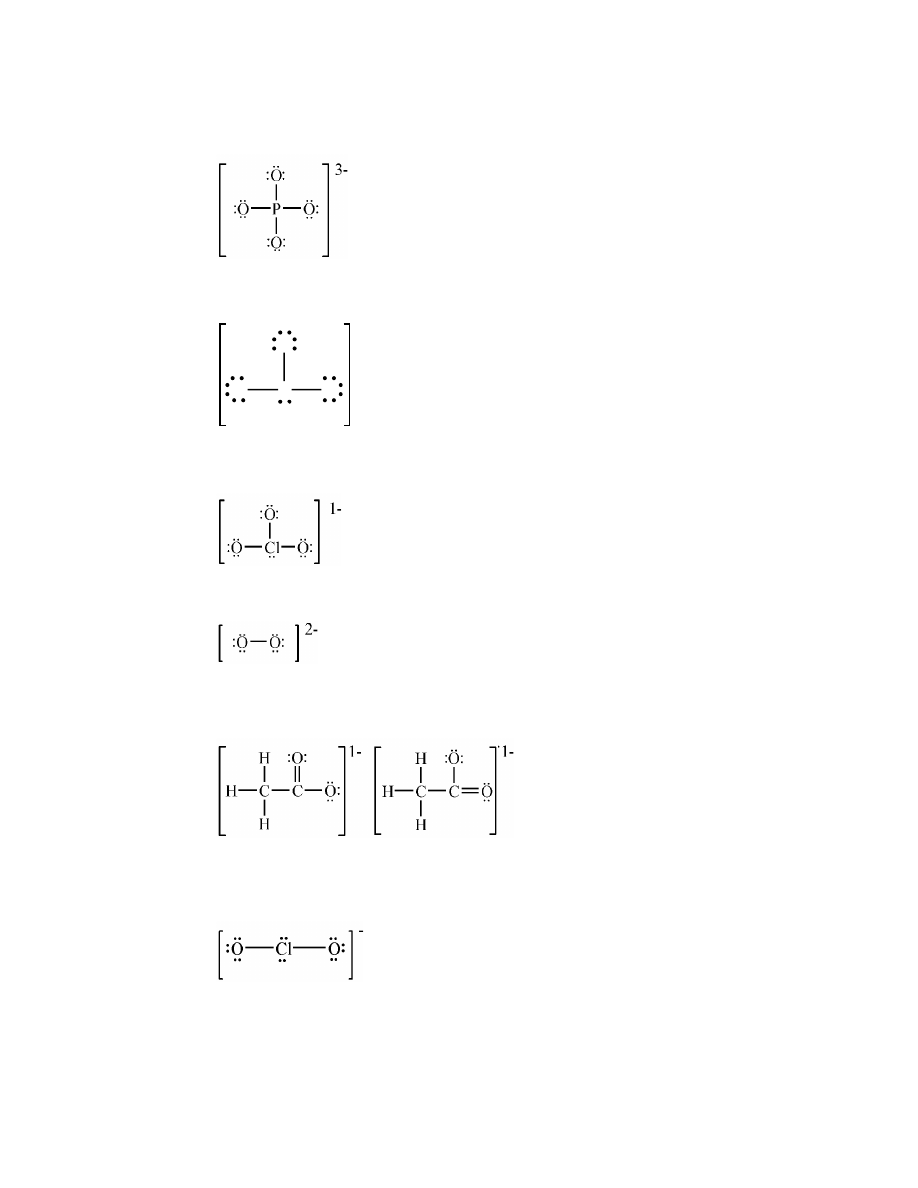

Here are three possible Lewis structures.

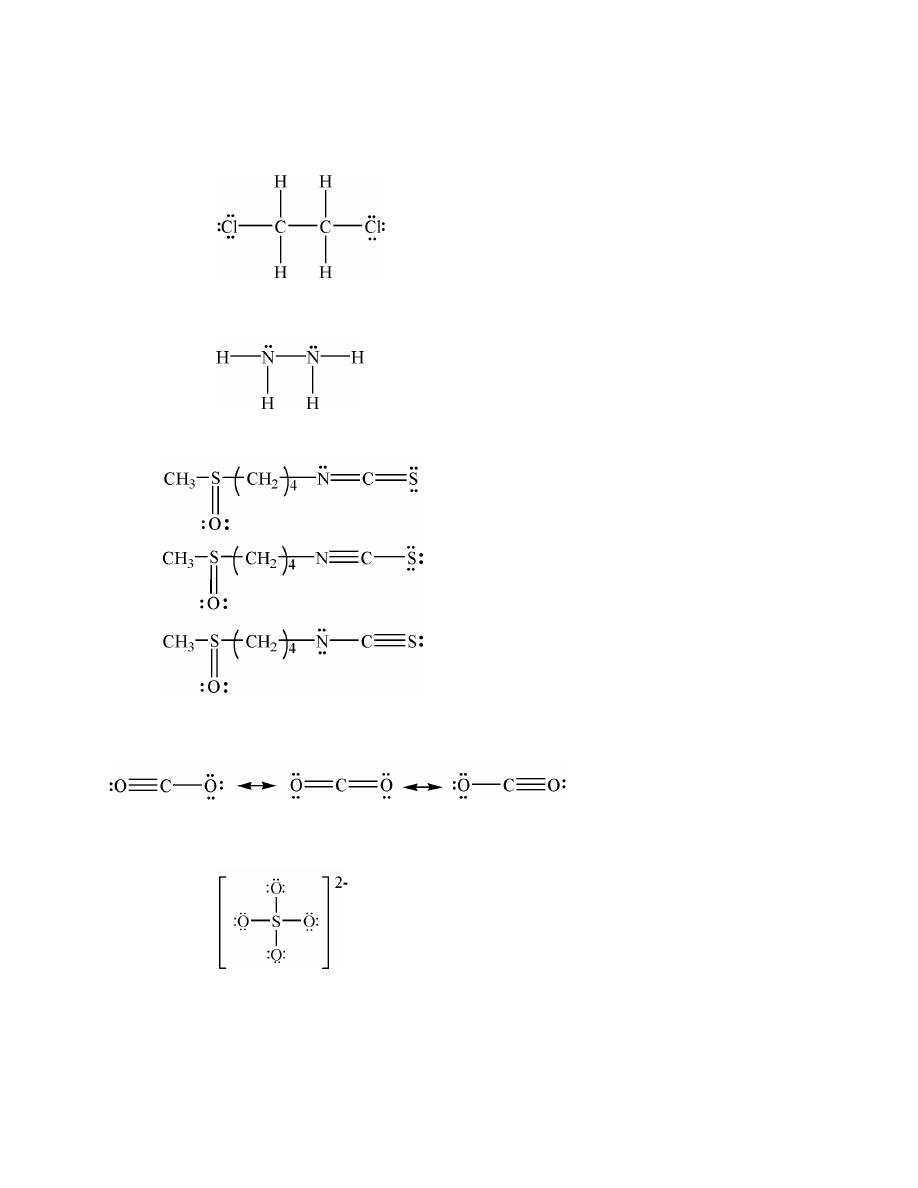

64.

C provides 4 valence electrons. Each oxygen provides 6 valence electrons. Having only 16 total v

alence electrons requires multiple bonding in the molecule.

65.

a.

S provides 6 valence electrons. Each O provides 6 valence electrons. The 2– charge

means two additional valence electrons. Total valence electrons = 32

248

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

b.

P provides 5 valence electrons. Each O provides 6 valence electrons. The 3– charge

means three additional valence electrons. Total valence electrons = 32.

c.

S provides 6 valence electrons. Each O provides 6 valence electrons. The 2– charge

means two additional valence electrons. Total valence electrons = 26

O

S

O

O

2-

66.

a.

Cl provides 7 valence electrons. Each O provides 6 valence electrons.

The 1– charge

means 1 additional electron. Total valence electrons = 26

b.

Each O provides 6 valence electrons.

The 2– charge means two additional valence

electrons. Total valence electrons = 14

c.

Each C provides 4 valence electrons. Each H provides 1 valence electron. Each O

provides 6 valence electrons.

The 1– charge means 1 additional valence electron.

Total valence electrons = 24

67.

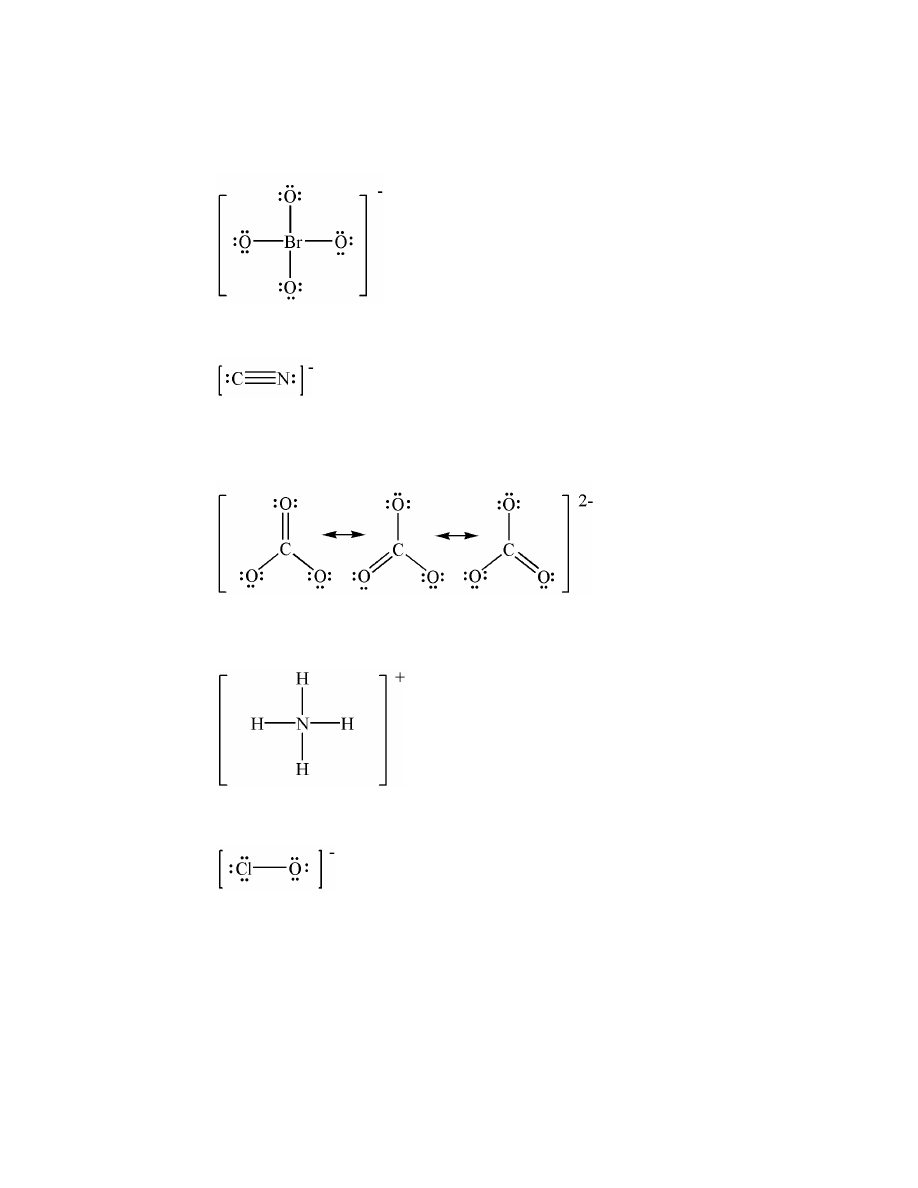

a.

Cl provides 7 valence electrons. Each O provides 6 valence electrons. The 1– charge

means one additional valence electron.

Total valence electrons = 20

249

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

b.

Br provides 7 valence electrons. Each O provides 6 valence electrons. The 1– charge

means one additional valence electron.

Total valence electrons = 32

c.

C provides 4 valence electrons. N provides 5 valence electron. The 1– charge means one

additional valence electron. Total valence electrons = 10

68.

a.

C provides 4 valence electrons. Each O provides 6 valence electrons. The 2– charge

means two additional valence electrons.

Total valence electrons = 24

b.

Each H provides 1 valence electron. N provides 5 valence electrons. The 1+ charge

means one less valence electron.

Total valence electrons = 8

c.

Cl provides 7 valence electrons. O provides 6 valence electrons. The 1– charge means

one additional valence electron. Total valence electrons = 14

69.

The geometric structure of the water molecule is bent (or V-shaped). There are four pairs of valen

ce electrons on the oxygen atom of water (two pairs are bonding pairs, two pairs are non-bonding

lone pairs). The H–O–H bond angle in water is approximately 105.

70.

The geometric structure of NH3 is that of a trigonal pyramid. The nitrogen atom of NH3 is surroun

ded by four electron pairs (three are bonding, one is a lone pair). The H–N–H bond angle is some

what less than 109.5 (due to the presence of the lone pair).

250

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

71.

BF3 is described as having a trigonal planar geometric structure. The boron atom of BF3 is surrou

nded by only three pairs of valence electrons. The F–B–F bond angle in BF3 is 120.

72.

The geometric structure of SiF4 is that of a tetrahedron. The silicon atom of SiF4 is surrounded by

four bonding electron pairs. The F–Si–F bond angle is the characteristic angle of the tetrahedron,

109.5.

73.

The geometric structure of a molecule plays a very important part in its chemistry. For biological

molecules, a slight change in the geometric structure of the molecule can completely destroy the

molecule’s usefulness to a cell, or can cause a destructive change in the cell.

74.

The general molecular structure of a molecule is determined by (1) how many electron pairs surro

und the central atom in the molecule, and (2) which of those electron pairs are used for bonding t

o the other atoms of the molecule. Nonbonding electron pairs on the central atom do, however, ca

use minor changes in the bond angles, compared to the ideal regular geometric structure.

75.

For a given atom, the positions of the other atoms bonded to it are determined by maximizing the

angular separation of the valence electron pairs on the given atom to minimize the electron repuls

ions.

76.

You will remember from high school geometry, that two points in space are all that is needed to d

efine a straight line. A diatomic molecule represents two points (the nuclei of the atoms) in space.

77.

One of the valence electron pairs of the ammonia molecule is a lone pair with no hydrogen atom a

ttached. This lone pair is part of the nitrogen atom and does not enter the description of the molec

ule’s overall shape (aside from influencing the H–N–H bond angles between the remaining valen

ce electron pairs).

78.

In NF3, the nitrogen atom has four pairs of valence electrons, whereas in BF3, there are only three

pairs of valence electrons around the boron atom. The nonbonding electron pair on nitrogen in N

F3 pushes the three F atoms out of the plane of the N atom.

79.

If you draw the Lewis structures for these molecules, you will see that each of the indicated atom

s is surrounded by four pairs of electrons with a tetrahedral orientation of the electron pairs (the a

rrangement in H2S is distorted because some electron pairs on the S atom are bonding and some a

re nonbonding).

80.

a.

four electron pairs in a tetrahedral arrangement with some lone-pair distortion

b.

four electron pairs in a tetrahedral arrangement with some lone-pair distortion

c.

four electron pairs in a tetrahedral arrangement

81.

a.

trigonal pyramidal (there is a lone pair on N)

b.

nonlinear, V-shaped (four electron pairs on Se, but only two atoms are attached to Se)

c.

tetrahedral (four electron pairs on Si, and four atoms attached)

251

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

82.

a.

tetrahedral

b.

trigonal pyramidal (there is a lone pair on P)

c.

non-linear, V-shaped (four electron pairs on O, but only two atoms are attached to O)

83.

a.

tetrahedral

b.

tetrahedral

c.

tetrahedral

84.

a.

basically tetrahedral around the P atom (the hydrogen atoms are attached to two of the

oxygen atoms and do not affect greatly the geometrical arrangement of the oxygen atoms

around the phosphorus)

b.

tetrahedral (4 electron pairs on Cl, and 4 atoms attached)

c.

trigonal pyramidal (4 electron pairs on S, and 3 atoms attached)

85.

a.

<109.5

b.

<109.5

c.

109.5

d.

109.5

86.

a.

approximately 109.5 (the molecule is V-shaped or nonlinear)

b.

approximately 109.5 (the molecule is trigonal pyramidal)

c.

109.5

d.

approximately 120 (the double bond makes the molecule flat)

87.

The bond angles would be expected to be slightly less than the 109.5° angle expected for four ele

ctron pairs due to one of the electron pairs being non-bonding.

88.

a.

V-shaped; 120° (one lone pair on Se with two S atoms attached, one with a double bond)

b.

trigonal planar; 120° (three S atoms attached to Se, one with a double bond)

c.

V-shaped; 120° (one lone pair on S with two O atoms attached, one with a double bond)

d.

linear; 180° (two S atoms attached to C, each with a double bond)

89.

Resonance is said to exist when more than one valid Lewis structure can be drawn for a molecule.

The actual bonding and structure of such molecules is thought to be somewhere “in between” the

various possible Lewis structures. In such molecules, certain electrons are delocalized over more t

han one bond.

90.

double

91.

repulsion

92.

Letter c is the correct answer. N–N contains equal electron sharing so it is nonpolar covalent.

252

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

93.

The bond with the larger electronegativity difference will be the more polar bond. See Figure 12.

3 for electronegativities.

a.

Br–F

b.

As–O

c.

Pb–C

94.

The bond energy of a chemical bond is the quantity of energy required to break the bond and sepa

rate the atoms.

95.

covalent

96.

In each case, the element higher up within a group on the periodic table has the higher electroneg

ativity.

a.

Be

b.

N

c.

F

97.

For a bond to be polar covalent, the atoms involved in the bond must have different electronegati

vities (must be of different elements).

a.

polar covalent

b.

covalent

c.

covalent

d.

polar covalent

98.

For a bond to be polar covalent, the atoms involved in the bond must have different electronegati

vities (must be of different elements).

a.

polar covalent (different elements)

b.

nonpolar covalent (two atoms of the same element)

c.

polar covalent (different elements)

d.

nonpolar covalent (atoms of the same element)

99.

Electronegativity differences are given in parentheses.

a.

N–P (0.9); N–O (0.5); the N–P bond is more polar.

b.

N–C (0.5); N–O (0.5); the bonds are of the same polarity.

c.

N–S (0.5); N–C (0.5); the bonds are of the same polarity.

d.

N–F (1.0); N–S (0.5); the N–F bond is more polar.

253

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

100.

In a diatomic molecule containing two different elements, the more electronegative atom will be t

he negative end of the molecule, and the less electronegative atom will be the positive end.

a.

oxygen

b.

bromine

c.

iodine

101.

In the figures, the arrow points toward the more electronegative atom.

a.

N–Cl: The atoms have very nearly the same electronegativity, so there is a very small, if

any, dipole moment.

b.

+ P N –

c.

+ S N –

d.

+ C N –

102.

(d); The formula for calcium nitride is Ca3N2 consisting of Ca2+ and N3–. The electron configurati

on for Ca2+ is: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6. Argon (Ar) is the noble gas with this same electron configuratio

n. The electron configuration for N3– is: 1s2 2s2 2p6. Neon (Ne) is the noble gas with this electron

configuration.

103.

a.

Na+

b.

I–

c.

K+

d.

Ca2+

e.

S2–

f.

Mg2+

g.

Al3+

h.

N3–

104.

a.

Na2Se: Na has one electron more than a noble gas; Se has two electrons fewer than a

noble gas.

b.

RbF: Rb has one electron more than a noble gas; F has one electron less than a noble gas.

c.

K2Te: K has one electron more than a noble gas; Te has two electrons fewer than a noble

gas.

d.

BaSe: Ba has two electrons more than a noble gas; Se has two electrons fewer than a

noble gas.

e.

KAt: K has one electron more than a noble gas; At has one electron less than a noble gas.

f.

FrCl: Fr has one electron more than a noble gas; Cl has one electron less than a noble gas.

254

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

105.

a.

Ca2+ [Ar]; Br– [Kr]

b.

Al3+ [Ne]; Se2–[Kr]

c.

Sr2+ [Kr]; O2– [Ne]

d.

K+ [Ar]; S2– [Ar]

106.

Relative ionic sizes are indicated in Figure 12.9.

a.

Na+

b.

Al3+

c.

F–

d.

Na+

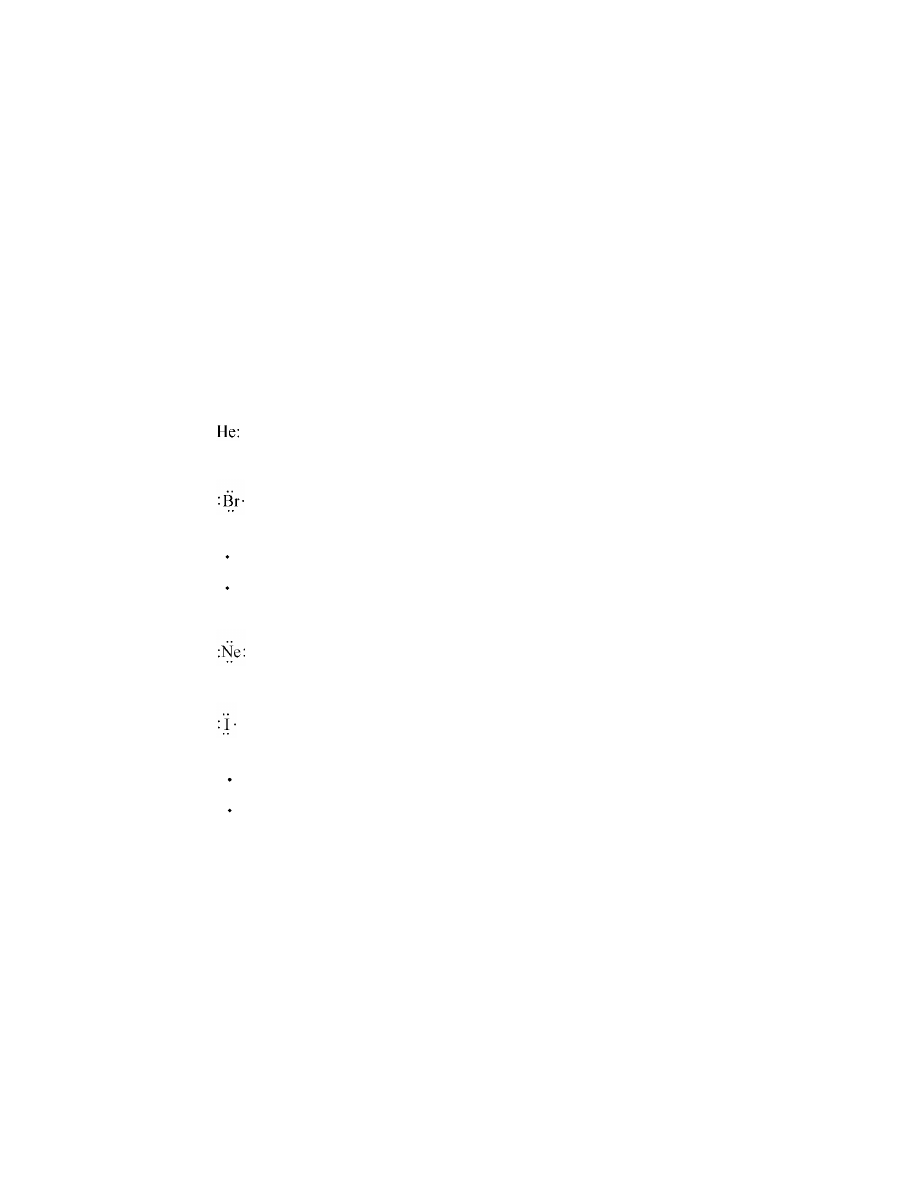

107.

a.

He

b.

Br

c.

Sr

Sr

d.

Ne

e.

I

f.

Ra

Ra

108.

a.

H provides 1; N provides 5; each O provides 6; total valence electrons = 24

b.

each H provides 1; S provides 6; each O provides 6; total valence electrons = 32

c.

each H provides 1; P provides 5; each O provides 6; total valence electrons = 32

d.

H provides 1; Cl provides 7; each O provides 6; total valence electrons = 32

109.

a.

GeH4: Ge provides 4 valence electrons. Each H provides 1 valence electron.

Total valence electrons = 8

255

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

b.

ICl: I provides 7 valence electrons. Cl provides 7 valence electrons.

Total valence electrons = 14

c.

NI3: N provides 5 valence electrons. Each I provides 7 valence electrons.

Total valence electrons = 26

d.

PF3: P provides 5 valence electrons. Each F provides 7 valence electrons.

Total valence electrons = 26

110.

a.

N2H4: Each N provides 5 valence electrons. Each H provides 1 valence electron.

Total valence electrons = 14

b.

C2H6: Each C provides 4 valence electrons. Each H provides 1 valence electron.

Total valence electrons = 14

c.

NCl3: N provides 5 valence electrons. Each Cl provides 7 valence electrons.

Total valence electrons = 26

d.

SiCl4: Si provides 4 valence electrons. Each Cl provides 7 valence electrons.

Total valence electrons = 32

256

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

111.

a.

SO2: S provides 6 valence electrons. Each O provides 6 valence electrons.

Total valence electrons = 18

b.

N2O: Each N provides 5 valence electrons. O provides 6 valence electrons. Total valence

electrons = 16

N

N

O

N

N

O

N

N

O

c.

O3: Each O provides 6 valence electrons. Total valence electrons = 18

112.

a.

NO3–: N provides 5 valence electrons. Each O provides 6 valence electrons.

The 1– charge means one additional valence electron. Total valence electrons = 24

b.

CO32–: C provides 4 valence electrons. Each O provides 6 valence electrons. The 2–

charge means two additional valence electrons. Total valence electrons = 24

c.

NH4+: N provides 5 valence electrons. Each H provides 1 valence electron. The 1+ charge

means one less valence electron. Total valence electrons = 8

113.

Beryllium atoms only have two valence electrons. In BeF2, there are single bonds between the ber

yllium atom and each fluorine atom. The beryllium atom of BeF2 thus has two electron pairs arou

nd it, that lie 180 apart from one another. For the water molecule, in addition to the bonding pairs

of electrons that attach the hydrogen atoms to the oxygen atoms, there are two nonbonding pairs o

f electrons that affect the H–O–H bond angle.

114.

a.

four electron pairs arranged tetrahedrally about C

b.

four electron pairs arranged tetrahedrally about Ge

c.

three electron pairs arranged trigonally (planar) around B

115.

a.

nonlinear (V-shaped, due to lone pairs on O)

b.

nonlinear (V-shaped, due to lone pairs on O)

c.

tetrahedral

257

1-

1-

1-

2-

2-

2-

+

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

116.

a.

ClO3–, trigonal pyramid (lone pair on Cl)

b.

ClO2–, nonlinear (V-shaped, two lone pairs on Cl)

c.

ClO4–, tetrahedral (all pairs on Cl are bonding)

117.

a.

< 109.5 (molecule is nonlinear, V-shaped)

b.

109.5 (molecule is tetrahedral)

c.

180 (molecule is linear)

d.

120 (molecule is trigonal planar)

118.

a.

nonlinear (V–shaped)

b.

trigonal planar

c.

basically trigonal planar around the C (the H is attached to one of the O atoms, and

distorts the shape around the carbon only slightly)

d.

linear

119.

a.

trigonal planar

b.

basically trigonal planar around the N (the H is attached to one of the O atoms, and

distorts the shape around the nitrogen only slightly)

c.

nonlinear (V-shaped)

d.

linear

120.

Ionic compounds tend to be hard, crystalline substances with relatively high melting and boiling p

oints. Covalently bonded substances tend to be gases, liquids, or relatively soft solids, with much

lower melting and boiling points.

121.

In a covalent bond between two atoms of the same element, the electron pair is shared equally an

d the bond is nonpolar; with a bond between atoms of different elements, the electron pair is uneq

ually shared and the bond is polar (assuming the elements have different electronegativities).

122.

Generally, covalent bonds between atoms of different elements are polar.

a.

nonpolar covalent

b.

ionic

c.

ionic

d.

polar covalent

e.

polar covalent

f.

nonpolar covalent

g.

nonpolar covalent

h.

ionic

123.

In general, an element farther to the right in a given period or an element closer to the top of a

given group is more electronegative.

P and Cl:

Cl

258

Chapter 12: Chemical Bonding

Ca and N:

N

N and As:

N

124.

O–F, P–Cl, P–F, Si–F; The greater the electronegativity difference between two atoms, the more

polar the bond between those two atoms.

125.

Relative ionic sizes are given in Figure 12.9. Within a given horizontal row of the periodic chart,

negative ions tend to be larger than positive ions because the negative ions contain a larger

number of electrons in the valence shell. Within a vertical group of the periodic table, ionic size

increases from top to bottom. In general, positive ions are smaller than the atoms they come from,

whereas negative ions are larger than the atoms they come from. If two ions contain the same

number of electrons, look at the nuclear charge. In general, the larger the nuclear charge, the

smaller the ion (electrons drawn closer to the nucleus).

a.

O2– > O– > O

b.

Fe2+ > Ni2+ > Zn2+

c.

Cl– > K+ > Ca2+

126.

Na+: 1s2 2s2 2p6

K+: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6

Li+: 1s2

Cs+: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p6 5s2 4d10 5p6

127.

(a), (b), and (d)

O

O

O

O

O

O

C

N

O

C

N

O

C

N

O

C

O

O

O

C

O

O

O

C

O

O

O

2

2

2

128.

Formula

Compound Name

Molecular Structure

CO2

carbon dioxide

linear

NH3

ammonia

trigonal pyramidal

SO3

sulfur trioxide

trigonal planar

H2O

water

bent or V-shaped

ClO4–

perchlorate ion

tetrahedral

259