2. NP-Movement in Passive Sentences

In passive sentences, the prepositional phrases are agent-phrases, and the moved

NP subjects are agentless-phrases.

(6) The city was destroyed by the enemy

agentless(patient) agent

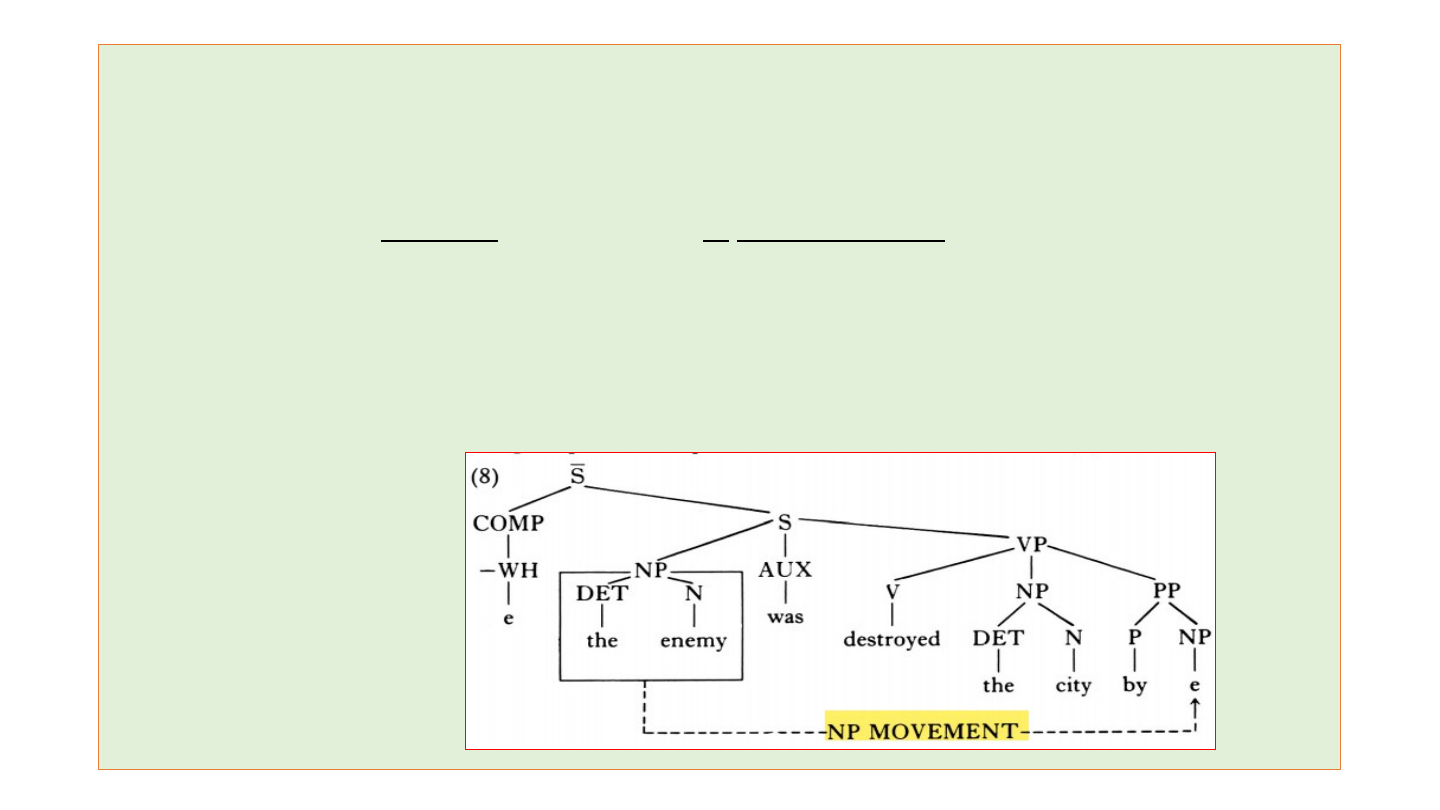

In the underlying structure before the generation of (6), the agent ‘the enemy’

appears

as a subject, and the subject ‘the enemy’ is moved to the positon after the preposi-

tion ‘by’

by NP-Movement, as in (8), when the agent role of ‘the enemy’ is preserved.

First NP-Movement:

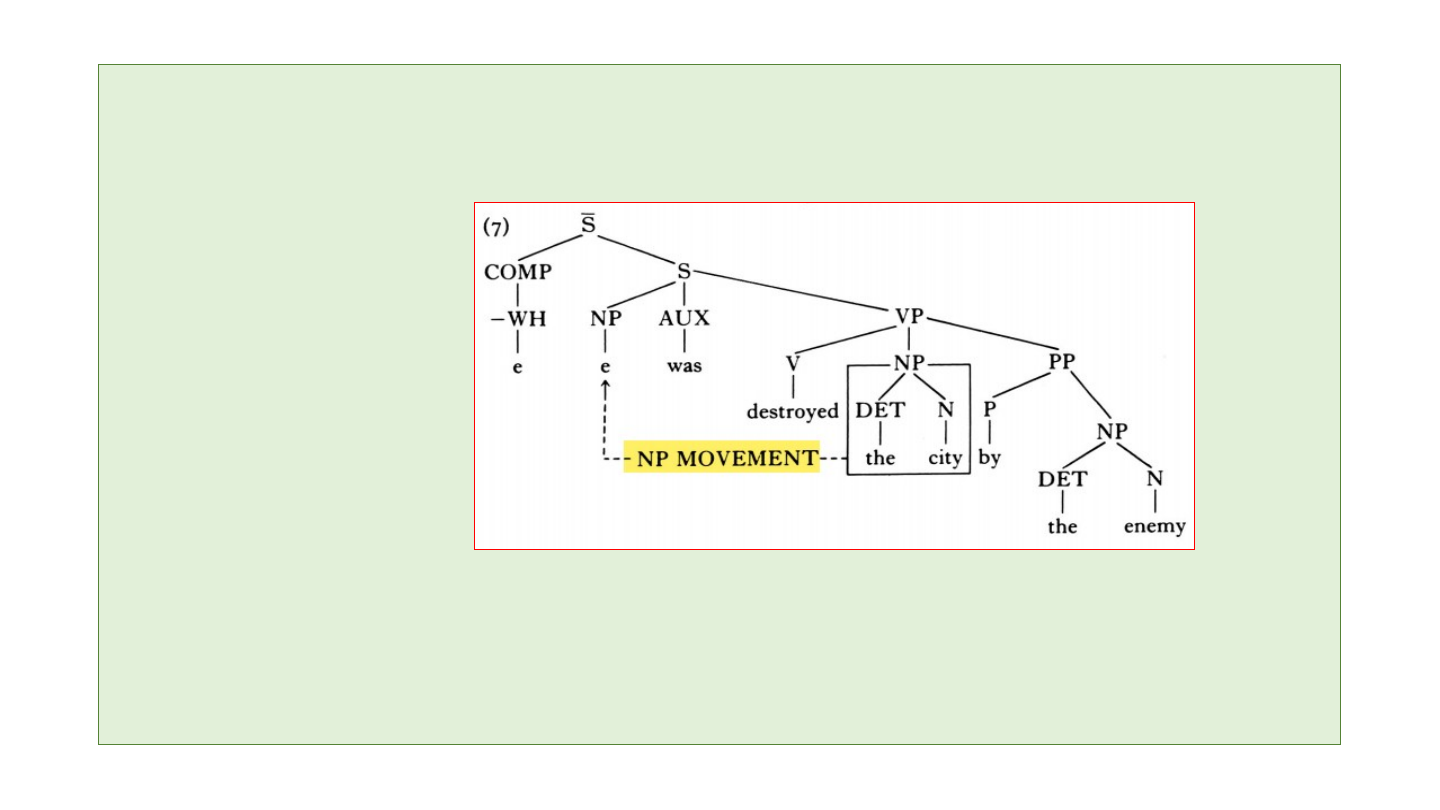

After that, the object ‘the city’ is moved to the empty position of the subject by anther

NP-Movement like (7), when the agentlessness of ‘the city’ is still preserved:

Second NP-Movement:

Therefore, by undergoing the two NP-Movement, the surface passive sentence (6) can be

derived. And when the two NPs are moved, the thematic role(agent or patient) of the NPs

is not changed.

3. NP-Movement in Raising

Another NP-Movement occurs in seem-clauses. The sentence (9) comprises two clauses:

the main clause and the subordinate clause.

(9) John seems to me to be unhappy.

[s[s John seems to me] [s to be unhappy]]

tensed clause untensed clause

The underlying structure of (9) can be ‘[s[s seems to me] [s John to be unhappy]]’.

Here, the subject ‘John’ in the subordinate clause cannot get a case from any categories,

since the subordinate clause is untensed(nonfinite). Only the verb in a tensed clause is

eligible to give a nominative case to the subject. So ‘John’ needs to be moved to the

position where it can get a case. On this occasion, the verb ‘seems’ in the main clause is

capable of attracting the subject ‘John’ into the subject position in the main clause which

is tensed(finite). So the NP(John)-Movement in this construction is known as RAIS-

ING.

♣ In syntactic structures, every NP must have a case in supporting of Case-Marking Rule.

▶ An evidence that ‘John’ in (9) originates as the subject of the subordinate clause can be

found in reflexive sentences. Recall that Reflexive Interpretation Rule – a reflexive is

construed with some preceding NP in the same clause which has the same number,

gender and person.

(11) John seems to me to have perjured himself.

(tensed clause) (untensed clause)

According to this rule, in a sentence (11), ‘himself’ must be construed with ‘John’

But how can this be? As you can expect, in the underlying structure, i.e. before the

NP-Movement, the ‘John’ was placed in the subject position in the subordinate

clause(perjured-clause), and then the ‘himself’ can be construed with the preceding NP

‘John’ in the same clause. Therefore, (11) obeys Reflexive Interpretation Rule.

However, the ‘John’ cannot get a case on this occasion. So the subject ‘John’ is raised to

the subject position in the main clause(seems-clause), and then ‘John’ in tensed

clause(seems-clause) can get a nominative case, satisfying Case-Marking Rule.

4. Supporting Argument for NP-Movement

[1] First Argument

If we suppose that the sentence (11) ‘John seems to me to have perjured himself’

consists of a single-clause structure in which ‘seems’ functions as some kind of

quasi-auxiliary, there is no way to account for the ill-formedness of the sentence (13).

(13) *John seems to me to have deceived myself.

If we assume that the seems-clause is a single-clause, the sentence (13) should be

grammatical, in which case, we’d expect to find that ‘me’ could serve as the

antecedent for an appropriate reflexive ‘myself’.

But this is not the case at all. (13) is actually ungrammatical in English: ‘myself’ cannot

be construed with ‘me’ here. Since there is no alternative antecedent for ‘myself’ in the

sentence, ‘myself’ is uninterpretable. The semantic interpretation is inappropriate.

Actually, ‘myself’ and ‘me’ are in different clauses: ‘me’ is part of the seems-clause and

‘myself’ is part of the deceived-clause. So the sentence (13) must have a two-clause

sentence. ‘John’ is the underlying subordinate clause subject, in the same clause as ‘myself’.

Therefore, the reflexive ‘myself’ is not construed with ‘John’ in underlying struc-

ture,

and so the Reflexive Interpretation Rule is not satisfied in underlying structure.

Although the ‘John’ is raised to the subject position in the main clause in surface

structure, in order to get a nominative case, the sentence (13) is ungrammatical.

In conclusion, the two facts can explain the grammaticality of (13). First, (13) consists

of two clauses: seems-clause and deceived-clause. Second, transformation of NP-Movement

between underlying structures and surface structures exists.

[2] Second Argument

A second argument is related to agreement facts. A predicate nominal agrees in number

with the subject of its own clause:

(14) They consider John to be a fool/*fools

The predicate nominal (a fool/fools) agrees with the subject ‘John’ of its own clause, not

with the subject ‘They’ of the main clause.

In the light of this observation, consider number agreement in a sentence (15):

(15) They seems to me to be fools/*fools

The predicate nominal ‘fools’ agrees with the NP ‘They’, in spite of the fact that the

two are contained in different clauses in surface structure. In fact, under the NP-Movement

analysis of seem-to-VP sentences, the sentence (15) pose no problem.

The ‘fools’ agrees with the underlying subject of its clause(subordinate clause),

and then the subject ‘They’ is moved to the surface subject position in the main clause

in order to get a nominative case.

So the transformation of NP-Movement in underlying structure can be sup-

ported.

In underlying structure, the number agreement between ‘they’ and ‘fools’ is ob-

tained.

[3] Third Argument

A third argument in favour of the NP-Movement analysis is related to Idiom Chunk NPs.

There are a limited set of idiom chunk NPs in English which are restricted to occurring

as the subject of certain specific expression:

(16) (a) The cat is out of the bag. (means ‘A secret is opened’)

(b) The fur will fly. (means ‘A great commotion breaks out’)

(c) The shit hit the fan. (means ‘The shit (abusive expression) slapped him’)

These subject idiom chunk NPs also occur in sentences as in (17):

(17) (a) The cat seems to be out of the bag.

(b) The fur seems to be flying.

(c) The shit seems to have hit the fan.

The NP-Movement analysis provides a proper account. The idiom chunk NPs occur

as the subjects of specific predicates in underlying structure; for under the NP-Move-

ment

analysis, the subject NPs in (17) originate in the underlined position as the subject of

the

idiomatic predicates concerned. At this time, the interpretation as idiom chunk NPs

can be satisfied.

After that, the subject NPs are moved to the subject position in seem-clause by NP-

Movement, actually in order to get a nominative case.

(17) (a) The cat seems to be out of the bag.

(b) The fur seems to be flying.

(c) The shit seems to have hit the fan.

Consequently, since the satisfied interpretations of the idiom chunks are caught in

underlying structure, the sentences (17) are grammatical and well-formed.